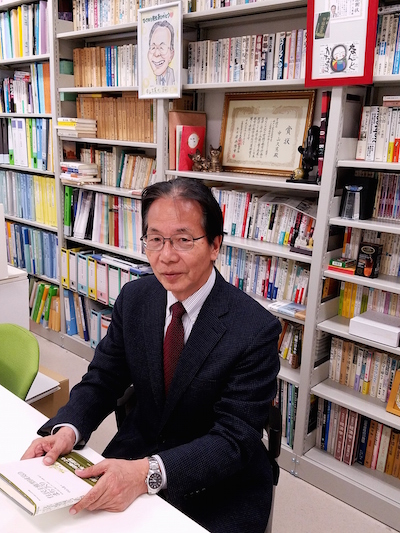

Hisanori Nakayama

Hisanori Nakayama

Professor

Kobe Gakuin University

Faculty of Contemporary Social Studies

Department of Social Studies of Disaster Management

Public Policy Program (’83)

Please tell us about your career path so far. What is your area of specialization and how did you come to work in this area?

After majoring in civil engineering at Osaka University’s Graduate School of Engineering, I began working for the Kobe City Government in 1975, and was later dispatched to Saitama University’s Graduate School of Policy Science (GSPS) where I obtained a master’s degree in political science in 1983. In my work at Kobe City Government, I was mainly involved in planning for transportation facilities, planning and implementation of urban development projects, creation of land use management plans and guidance concerning regulations, guiding and working on resident-led town planning, and the planning and implementation of earthquake reconstruction projects.

When the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake struck in 1995, I was working as the head of the town planning office in Kobe’s Hyogo ward and was in charge of gathering opinions from the public and publishing the ward’s PR magazine, but after the earthquake I focused all of my energy on procedures for rebuilding the lives of residents and supporting residents in earthquake reconstruction projects. I subsequently went on to promote resident participation in earthquake reconstruction projects, and oversaw HR and financial support work for the town planning councils established in districts where reconstruction projects were being implemented. Until my retirement in 2009, I was given overall responsibility for reconstruction work, and pushed forward and guided the projects and procedures necessary to complete the reconstruction.

After the Great East Japan Earthquake that struck in 2011, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism wanted to make use of my experience in the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake and appointed me as a supervisor under their direct jurisdiction for overseeing surveys and work in the area, and I supported work on a reconstruction plan for Natori in Miyagi prefecture. These days, as well as teaching as a professor in the Department of Social Studies of Disaster Management at Kobe Gakuin University’s Faculty of Contemporary Social Studies, I try to pass on my experience in reconstruction projects after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake to my students and the general public through my writing activities.

You were working for the Kobe City Government when the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake occurred in 1995. Please tell us about your role in the reconstruction projects after the earthquake.

As the head of the town planning office in Hyogo ward, immediately after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake I was on the front line and closest to the victims in the affected areas. I undertook or provided support for different roles such as distribution of emergency relief aid, evacuation center work, applications for demolition of damaged houses, donations, issuing victim certificates, moving into and maintaining emergency temporary housing. Around three months after that, I was put in charge of support for reconstruction town planning projects until 1996.

As the head of the town planning office in Hyogo ward, immediately after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake I was on the front line and closest to the victims in the affected areas. I undertook or provided support for different roles such as distribution of emergency relief aid, evacuation center work, applications for demolition of damaged houses, donations, issuing victim certificates, moving into and maintaining emergency temporary housing. Around three months after that, I was put in charge of support for reconstruction town planning projects until 1996.

In the four years from 1997 to 2000 I was head of town planning support in the Urban Design Office of the Urban Planning Department where I was in charge of support for the activities of the town planning councils established in the districts in which reconstruction projects were being implemented. I was also responsible for ensuring the Kobe City Town Planning Ordinance, which promotes resident-led projects, was applied appropriately and pushed forward these joint projects between the city government and earthquake victims.

In the five years from 2005 to 2009, my roles included being the head of the Zoning Department in the General Urban Planning Office and the head of the Urban Development Office as well as an advisor to the city government and being responsible for land zoning and redevelopment works in earthquake reconstruction projects. I also undertook a range of administrative procedures towards the end of the projects, including applications for government subsidies and their use, works approval, changes in urban planning, and coordinated the complex interests of stakeholders such as calculation of compensation and settlements, administrative sanction procedures, and court cases, etc..

How have you shared and employed the knowledge and expertise gained in dealing with the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in subsequent disasters, such as the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in 2011, and the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake?

Immediately after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism told me they wanted me to make use of my experience in the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake so they appointed me as a supervisor under their direct jurisdiction for overseeing surveys and work in the area, and I supported work on a reconstruction plan for Natori in Miyagi prefecture in FY 2011 and participated in the 12 meetings that were held. For the two years from 2014 to 2015 I was appointed as a member of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism’s Town Planning Verification Committee for Reconstruction after Tsunami Damage in the Great East Japan Earthquake, and I offered counsel regarding verification and evaluation of reconstruction projects and town planning for five years after the earthquake, including comparisons with the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake.

Immediately after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism told me they wanted me to make use of my experience in the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake so they appointed me as a supervisor under their direct jurisdiction for overseeing surveys and work in the area, and I supported work on a reconstruction plan for Natori in Miyagi prefecture in FY 2011 and participated in the 12 meetings that were held. For the two years from 2014 to 2015 I was appointed as a member of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism’s Town Planning Verification Committee for Reconstruction after Tsunami Damage in the Great East Japan Earthquake, and I offered counsel regarding verification and evaluation of reconstruction projects and town planning for five years after the earthquake, including comparisons with the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake.

From 2011 up to the present, every summer I have conducted onsite surveys and interviews with administrative officials and victims from Iwate prefecture to Fukushima prefecture for the purposes of fixed point observation concerning the reconstruction status of areas affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake.

In the Kumamoto earthquakes that occurred along an inland active fault, I conducted an onsite survey, interviewing stakeholders in the summer of 2016. In 2017 I implemented an onsite survey as an advisor as to whether or not the reconstruction project methods from the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake could be used in reconstruction projects in Mashiki as well as gathering opinions from those in charge at the Kumamoto prefectural office.

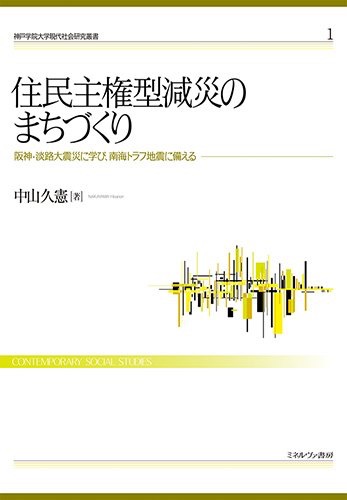

Also, as an author who wants to hand down his experience of involvement in reconstruction projects in the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, I have published books entitled “Kutō – Moto no Machi ni Sumitai n’ya! – Kōbe-shi Minatogawa-chō Jūmin Shutai no Shinsai Fukkō Machi-zukuri –“ (Struggle – I Want to Live in the Town Like it Was Before – Resident-led Earthquake Reconstruction Town Planning in Minatogawa, Kobe”, Koyoshobo, 2008), “Kōbe no Shinsaifukkōjigyō – 2 Dankaitoshikeikaku to Machi-zukuri Teian - ”(Earthquake Reconstruction Projects in Kobe – Two-stage Town Planning Proposals”, Gakugei Publishing, 2011), and “Jūmin Shukengatagensai no Machi-zukuri – Hanshin Awaji Daishinsai ni Manabi, Nankai Torafu Jishin ni Sonaeru - ” (Resident-led Town Planning for Disaster Risk Reduction – Learning from the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake – Preparing for an Earthquake in the Nankai Trough”, Minerva Shobo, 2015). I hope they are useful for officials in cities affected by disasters and in projects implemented by groups involved in town planning.

Also, as an author who wants to hand down his experience of involvement in reconstruction projects in the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, I have published books entitled “Kutō – Moto no Machi ni Sumitai n’ya! – Kōbe-shi Minatogawa-chō Jūmin Shutai no Shinsai Fukkō Machi-zukuri –“ (Struggle – I Want to Live in the Town Like it Was Before – Resident-led Earthquake Reconstruction Town Planning in Minatogawa, Kobe”, Koyoshobo, 2008), “Kōbe no Shinsaifukkōjigyō – 2 Dankaitoshikeikaku to Machi-zukuri Teian - ”(Earthquake Reconstruction Projects in Kobe – Two-stage Town Planning Proposals”, Gakugei Publishing, 2011), and “Jūmin Shukengatagensai no Machi-zukuri – Hanshin Awaji Daishinsai ni Manabi, Nankai Torafu Jishin ni Sonaeru - ” (Resident-led Town Planning for Disaster Risk Reduction – Learning from the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake – Preparing for an Earthquake in the Nankai Trough”, Minerva Shobo, 2015). I hope they are useful for officials in cities affected by disasters and in projects implemented by groups involved in town planning.

You are currently a Professor at Department of Social Studies of Disaster Management of Kobe Gakuin University. Please tell us what projects you are currently involved in.

① At Kobe Gakuin University, I teach classes on disaster prevention in the form of administration for disaster prevention and disaster prevention town planning theory for second grade students, and research into the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake to the third grade students.

② As head of the university library and information support center, I am in charge of improving, developing and managing facilities, and am pushing forward support for learning and research for 11,000 students and teachers in nine faculties. ③ As a registered specialist of the Land Readjustment Center, I also deliver talks about how to implement administrative work in the event of a disaster and how to implement reconstruction projects in response to dispatch requests from prefectures, cities and organizations throughout the country.

③ As a registered specialist of the Land Readjustment Center, I also deliver talks about how to implement administrative work in the event of a disaster and how to implement reconstruction projects in response to dispatch requests from prefectures, cities and organizations throughout the country.

④ I am one of the members of the “U.S-Japan Grassroots Exchange on Post-Disaster Community Building” (20 people from the four cities of Kobe – affected by the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, Miyako – affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake, New Orleans – affected by Hurricane Katrina, and Galveston – affected by Hurricane Ike) led by the East-West Center in Hawaii. The project has a grant for this project from the Japan Foundation from 2015 to 2017, and in 2015 there was a visit by the US members to Japan while in 2016 we visited the United States. In the winter of 2017, there is to be a general review of the project in the US in which I will participate and we will have an exchange of opinions about disaster reconstruction in both countries and the affected areas, and bring the project to a conclusion.

What have been some of the biggest challenges you have faced in your work? And what have been the most interesting or rewarding aspects of your career?

The things that I have been most deeply involved in for the greatest amount of time in my career are the range of aspects I was responsible for in the reconstruction after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake. One of the issues I faced then was coordination between the national and prefectural government and organizations in the city as a way of taking forward work for the administration to achieve the quickest possible reconstruction, and what I tried to do was see things from the point of view of the victims and make the speed with which progress was made the main issue. This involved getting the victims to tell me what their real thoughts and feelings were and ensuring the city government’s response did not favor some victims over others. In other words, this meant listening to what resident leaders involved in town planning activities had to say and coordinating opinions with the dispatched specialist consultants to enable a shared understanding of what was to be prioritized. What I felt was really worthwhile in all of this were the frank comments I received from residents of the affected areas who said that while a lot had happened they were pleased that the city had recovered and was now a great place. I felt that such comments contained heartfelt gratitude towards all of the officials who had been involved in the projects. While reconstruction projects always involve land and thus people have differing interests and there are pros and cons, these comments also show that as an official from local government who was involved for a long period in these projects I managed to do my work fairly and justly for the residents without putting anyone at an unfair advantage or disadvantage.

In your capacity as disaster management expert, what are the biggest challenges Japan is currently facing and what can be done to enhance Japan’s disaster preparedness.

They say disasters come once you have forgotten about them, and natural disaster always occur at fixed intervals. The reality is that we can’t avoid an earthquake directly under the capital, or an earthquake in the Nankai trough, or a 900 hpc class super typhoon. Furthermore, as became apparent in the Great East Japan Earthquake, while it is possible to deal with massive once-in-a-thousand-year disasters using technology, huge construction projects that consume state budgets will ultimately turn out to be white elephants. On top of this, as a decreasing population becomes a reality, decreased regional finances and fewer public officials is an unavoidable fact.

Rather than the kind of disaster prevention that relies on government like we have seen so far, the road forward is “disaster reduction” that involves anticipation and the prior securing of safe places in order to at the very least save the lives of everyone through resident-led evacuation. The foundation for achieving this will be to aim for my idea of “town planning for citizen-led disaster reduction” (see my book of the same name) in which residents themselves create organizations such as town planning councils, think for themselves, and do the things they can do themselves while leaving the things they can’t do up to the government. In addition, we will have to change the legal system, which relies on the government in such situations, and people will always protect themselves from disasters while taking on the long-term challenge of rebuilding towns and cities to be compact.

What led you to GRIPS/GSPS? What is the most important thing you got out of your studies here, and how has your experience at GRIPS/GSPS prepared you for future endeavours?

I have always wanted to make provincial Japan a better place, and after joining the city government in Kobe where I grew up I took an anti-Tokyo, anti-centralization stance and strived for regional devolution. However, Japan was still going through its period of rapid growth during my two years at GSPS, so when it came to how to proceed with projects in my specialist field of urban planning I couldn’t help but believe the myth that if you continuously implement policies for growth and expansion under centralized authority then things keep getting better. Furthermore, I learned that in life in Saitama and the greater Tokyo area, money, resources, and information are far more concentrated than in Kobe, and was really taken aback by how in comparison Kobe was nothing more than a grand city in the countryside. After going back to Kobe having gained an understanding of this reality, I decided that Kobe is fine as a countryside city, and using the approach to policy setting I had learned in my policy studies at GSPS I took up the challenge of a land use plan that involved shrinking the city, and went against thinking at that time, and implemented it. I then experienced the “lost two decades” and the collapse of the bubble and the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, and this enabled me to fully understand whose hands policy making decisions should be in. Now that the reconstruction work is complete, it has reaffirmed to me that I was glad I was in the countryside in Kobe because the fact that I was able to think of and implement a policy gave me confidence as a planner. If I had been in the Tokyo area I wouldn’t have been able to do anything like this myself. Currently, at the university in Kobe, I advise students who are attracted to Kobe and came here to study from different regions around Japan that their hometown is the best place for them and they should get a job that allows them to go back there if possible (such as a local public official, police officer, or fire fighter). If I didn’t have the two years of experience at GSPS I wouldn’t have the standards for thinking and acting that I do now, so in these terms it was a really great two years.

What are some of your fondest memories of your time spent at GRIPS/GSPS?

More than anything, meeting and being taught by my former teacher and current honorary president Toru Yoshimura. Recently I was fortunate enough to meet him for the first time in a while, and to be able to spend time speaking with him. He’s in his 80s now but is full of energy, and as always I was overwhelmed by his constant stream of amazing ideas, none of which I had thought of myself before. The freshness of these ideas gave my own brain circuitry a new lease of life, and I felt as if I was a student once again.

Thinking back through my memories of my two years at GSPS in Saitama, a certain event gave rise to the need to prevent the unauthorized entry of strangers to the research building. When this happened, graduate students came together to act, which led to the forming of the Student Council of which I was the first president. This is a great memory for me. 36 years have passed since then, and one of the activities of the council that I particularly remember is holding a party with not only teachers at GSPS but also teachers from overseas and the students giving a live music performance. Another great memory is when I took photographs of second-year students who were about to finish their studies as they went about their lives doing research, and I created a photo album and gave it to them.

In those days students studied for two years, so while there were hierarchical relationships, we still discussed heatedly the current political and economic issues from the perspectives of the groups we came from and from our own perspective. This is a great memory, and the fact that I was able to hear stories from behind the scenes is also a great memory.

How would you like to stay involved with the School? Do you have any suggestions on how to further utilize the GRIPS alumni network?

As a graduate, I want to maintain my relationship with my old school GRIPS/GSPS if possible, but sadly I have almost no opportunities to do so. I hope that if any of the students I studied with or my seniors/juniors are reading this interview that they will get in contact with me. I hope that through this the alumni network will grow, even if it is just by a little.