|

|

|

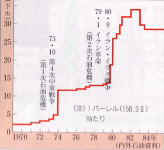

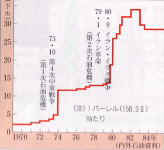

| Kakuei Tanaka's book proposed to rebuild Japan by massive public investment in transportation infrastructure. | The crude oil price (USD/barrel). | Panicked consumers rushed to supermarkets to buy up toilet paper. |

(See Handout no.12)

As noted in the previous lecture, Japan's high growth came to an end in the early 1970s. On average, the growth rate fell to about 4% in the 1970s and 80s, and further down to near zero in the 1990s. Why did growth slow down in the early 1970s? What happened then?

One important fact that we should keep in mind is that this growth slowdown was common to all industrial countries, including those in North America and Western Europe. So the reasons for slowdown must be (at least partly) global, although domestic factors may have played a role. In addition, inflation accelerated in all industrial countries in the 1970s. This also points to a globally common cause.

Let us look at the domestic and international reasons for Japan's slowdown in turn.

On the domestic side, transition to lower growth was natural and inevitable because the Japanese economy had caught up with the US and European economies and matured. During the catching up process, a developing country can (selectively) import technology and new systems which exist in the developed world. But when you become part of the developed world, you can no longer copy others but must create something new in order to grow. Naturally, clearing your own path is harder and slower than following someone else's path.

In terms of per capita GNP (measured in actual dollars, not PPP dollars--see below), the income ratio between Japan and the US was 1 to 14 in 1950, 1 to 6 in 1960, and 1 to 2.5 in 1970. This narrowing of income gap was of course the result of Japan's much faster growth compared with the US. After the 1970s, the yen/dollar exchange rate fluctuation began to disturb this income comparison. The income ratio was 1 to 1.3 in 1980 and 1 to 0.93 in 1990 (this means Japanese income was temporarily higher than US income). But since Japanese prices were in general much higher than in the US, this does not necessarily mean the Japanese people had attained a higher living standard than the Americans in 1990.

In terms of per capita income at purchasing power parity (PPP), Japan surpassed Italy in 1966 and the UK around 1975. Japan did not overtake the US, West Germany or France but came close to their income levels by the mid 1970s. Thus, we can say that Japan was firmly in the highest income group by the 1970s.

Purchasing power parity (PPP) is a hypothetical exchange rate adjusted for the difference in prices. Since price levels differ from one country to another, the same amount of money sometimes buys a lot and other times only a little. In Japan, prices are high so $1 (or its yen equivalent) buys less than in, say, China. This adjustment is necessary to compare income and living standards across countries correctly.

Another way to measure income is by affordability of consumer durables. It took 10.7 months of average salary to buy a new car (most basic model) in 1966, but Japanese workers had to work only 4.0 month to buy a car in 1974. In 1991, a new car could be had after 2.4 months of working. By the 1970s, virtually all Japanese households were equipped with washing machines, refrigerators, vacuum cleaners, telephones and color TVs (automobiles and air-conditioners were not as widely owned because they were not necessary for some households).

On the external side, there were two major international economic shocks in the 1970s which were common to all countries: the oil shocks and the beginning of general floating of major currencies. These are now examined more closely.

The price of crude oil was low and stable for a long time in the post WW2 period. But in autumn 1973, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) decided to raise its price dramatically from $2 to $11/barrel and reduced their export volume to industrial countries by about 10%. The oil price was again raised to about $30/barrel in 1979-80. Both of these price increases were associated with political and military situations in the Middle East. The first oil shock was the result of the Fourth Middle Eastern War and the second oil shock was in response to the Iranian Revolution.

The OECD countries depended heavily on imported oil (67% of domestic use on average) but Japan's foreign oil dependency was particularly high (99.7%). In Japan, the first oil shock caused both WPI and CPI inflation to surge (between them, WPI rose faster) beyond what could be explained by the pure oil impact. People were thrown into panic and tried to hoard as many daily necessities as possible, such as toilet paper, soap and kerosene. But this stocking behavior collectively led to empty shelves in supermarkets, although the flow supply was sufficient to cover the flow demand. Seeing empty shelves, people panicked even more. This was called kyoran bukka (crazy prices). Shortage was also observed in industrial inputs.

In 1974, Japan registered the first negative growth (-0.8%) in the postwar period. This was called "stagflation" (recession in the midst of high inflation).

On close examination, however, money supply was increasing rapidly and inflation was already accelerating in the early 1970s well before the first oil shock. This was due to the Bank of Japan's foreign exchange intervention to support the dollar (massive dollar buying with little sterilization). Moreover, fiscal policy was expansionary in the early 1970s driven by prime minister Kakuei Tanaka's "Japanese Archipelago Rebuilding Plan" (active public investment for large-scale transportation infrastructure).

After the first oil shock and "crazy prices," prime minister Tanaka's "Rebuilding Plan" was abandoned. Monetary policy was also gradually tightened. The Bank of Japan was severely criticized for causing a serious inflation, and in response, it became more "monetarist." The Bank of Japan began to target lower monetary growth to avoid further inflation.

|

|

|

| Kakuei Tanaka's book proposed to rebuild Japan by massive public investment in transportation infrastructure. | The crude oil price (USD/barrel). | Panicked consumers rushed to supermarkets to buy up toilet paper. |

As a part of structural reform, the government tried to reduce energy consumption and promote "rationalization" (consolidation and closure) of energy-intensive industries including paper and aluminum refining. The national campaign was started to turn off unnecessary lights, set the room temperature lower in winter or higher in summer, and so on. Saving energy took time to implement, but eventually it was quite successful. By the early 1980s Japan became the most efficient energy user among industrial countries. The Japanese car companies also succeeded in mass producing energy-efficient cars, many of which were exported to overseas markets, especially the US (see the story of Soichiro Honda in lecture 11).

Compared with the first oil shock, the second oil shock had a relatively minor impact on Japan. Inflation rose but not very much and the economy continued to grow.

Many economists all over the world debated the nature of the oil shocks. There were two diametrically opposed interpretations of the oil shocks, and the debate is still unresolved. Jeffrey Sachs, Michael Bruno and Barry Bosworth (among others) took the first position. Hans Genberg, Alexander Swoboda and Ronald McKinnon (plus Kenichi Ohno) took the second position.

The supply shock view: the first--and more popular--view says that the oil shock was a supply shock caused by OPEC's political power. As the oil price was raised exogenously, the aggregate supply curve shifted up and to the left (think of the standard IS-LM-AS-AD model). This led to higher price and lower output, namely, "stagflation." Additionally, aggressive wage increases by trade unions contributed to the global inflation. In order to cope with this situation, the world must solve its supply side problems including energy shortage and wage rigidity.

The global monetarist view: the alternative view argues that the high inflation was caused by global monetary expansion, which in turn was caused by the breakdown of the Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate system. As the Japanese and European central banks tried to buy up dollars to prevent the sharp appreciation of their currencies against the dollar during 1971-73, money supply was increased in all major countries. Global excess liquidity ignited commodity price inflation even before the first oil shock broke out. The oil shock was the final result and not the cause of high inflation which was generated by the oversupply of global money. The OPEC is always aggressive, but their attempt to raise the oil price succeeds only when there is too much global liquidity. Thus, the stagflation in the 1970s should be explained by the instability of the international monetary system.

|

|

President Nixon went on TV to announce the end of the Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate system (Aug. 15, 1971). |

The Bretton Woods system (1944-71) was a dollar-based and US-centered fixed exchange rate system. It achieved unprecedented global price stability, high growth and trade liberalization from the 1950s onward. But the system began to show strain in the mid 1960s.

As the US (center country) began to adopt an expansionary macroeconomic stance, global inflation emerged in the late 1960s. There was a downward pressure on the dollar and corresponding upward pressure on gold and the European and Japanese currencies in the foreign exchange market. In August 1971, US President Richard Nixon finally announced that the US dollar was no longer fixed to gold, and the dollar began to float. But the Bank of Japan and the central banks in Europe intervened massively to purchase the dollar to avoid the appreciation of their currencies against the dollar. From 1971 to 1973, the world tried to re-peg the major currencies at new exchange parities, but the effort failed. Under severe speculative attacks, the world entered into an era of floating major currencies in early 1973.

Since then, the general floating has continued to this date. Soon, it was discovered that pure float was too volatile and injurious to national economies. In 1985, the Group of Five (G5)--US, Japan, West Germany, France, UK--jointly intervened to lower the overvalued dollar (Plaza Agreement). In 1987, the Group of Seven (G7)--G5 plus Italy and Canada--again intervened to stabilize the dollar at a now lower level (Louvre Accord). After that, such joint interventions have been tried occasionally to correct extreme currency movements.

The Japanese economy is particularly vulnerable to the fluctuation of the yen/dollar rate since (i) the yen is a lone floater; there no yen zone in Asia unlike the euro area in Europe or the global dollar zone for the US; (ii) most of Japan's trade and virtually all financial transactions are conducted in dollar; (iii) Japan as the largest creditor country holds a huge amount of unhedged dollar assets which are concentrated in US government bills and bonds, whose values depreciate whenever the dollar falls; and (iv) Japanese industries have relatively low exchange rate pass-through and high domestic value-added contents. When the yen becomes overvalued, Japanese output and investment stagnate, prices and wages are suppressed, and financial strain is created.

Some argue that the Japanese economic system of the 1950s and 60s, based on long-term stable relationships like the main bank system, lifetime employment and active official guidance, became obsolete by the 1970s. This system functioned well while the country was in the catching up process, but was no longer appropriate for a more mature industrial society. They say that Japan should have shifted toward a more market-based, less officially guided system during the 1970s.

But two big shocks (oil shocks and floating currencies) intervened, and the Japanese government was forced to mainly tackle these macroeconomic problems instead of concentrating on systemic transformation. As a result, and even now, the Japanese economy has retained many legacies of the catching-up process such as over-regulation and the lack of incentive for innovation. This has become the institutional barrier for Japan's further development.

This is one view. However, others contend that Japan should not embrace the US-type free economy. They argue that Japan's transformation into a freer market economy, if it is to be done, must be implemented gradually and carefully, without throwing away the desirable Japanese features including long-term perspective, team-work spirit, balancing efficiency and equity, and so on.

Japan's main external problem in the 1950s to mid 1960s was how to cope with an emerging trade deficit (recall the "balance-of-payments ceiling" and "stop-go policy" in lecture 11). But after the mid 1960s, the problem shifted to the opposite: how to reduce its huge trade surplus. The trade surplus was politically undesirable for Japan because it angered the US (especially the Congress and industrial lobbies). Especially after the 1980s, Japan recorded the largest trade surplus and the US had the largest trade deficit in the world year after year. Furthermore, the size of Japan's surplus and that of the American deficit were similar. Japanese saving was used to finance American overspending, and that became the largest financial flow in the world economy.

|

|

| Japanese cars bound for export markets. | Japan-US trade negotiation (Strategic Impediment Initiative, 1989) |

The history of Japan's trade friction with the US (and, to a lesser extent, with the EU) is long and highly politicized. It began in the 1960s when Japan was exporting cheap textile products ("one-dollar blouse") to the US market. After that, one by one, a number of Japanese goods came under attack: steel, TV, metalworking machine, automobile, video player, semi-conductor, and so on. From the 1980s, in addition to the pressure to export less, the US also began to demand that Japan buy more American goods including farm products like orange and beef, automobile parts, construction and financial services, and so on. The US also argued that the Japanese economic system was inefficient and closed to imports so it must be reformed.

Professor Ronald McKinnon (Stanford University) and I wrote a book on how to interpret this bilateral economic friction (see the reference below). Our view is in the minority in the US but there are many people in Japan who agree with our analysis. The McKinnon-Ohno hypothesis of the "Syndrome of the Ever-higher Yen" says:

--Every several years when the US trade deficit with Japan becomes politically intolerable, the US demands two things: (i) the yen must be appreciated; and (ii) Japan must buy more from and sell less to the US. This happened in 1971-73, 1977-78, 1985-87, and 1993-95. As the US high officials (typically the Secretary of Treasury, sometimes even the President) talk up the yen, the yen sharply appreciates and the trade tension rises between Japan and the US.--But this only destabilizes the Japanese and Asian economies without solving the US trade deficit problem. The US deficit is a long-term, structural problem caused by the saving shortage of American government and households. Currency adjustments or trade talks cannot solve this US-made problem. The fundamental solution must come from the American domestic policy to curb consumption and encourage saving.

--Japan should open up its economy and accept more imports from developing countries (not just from the US) and FDI from abroad. This will be good for Japan's micro and structural reforms. However, it may have little impact on the trade balance which is basically determined by the savings-investment relationship at the macro level. Japan and the US should conclude bilateral agreements to (i) solve trade disputes at the micro or sectoral level (or take it to WTO); and (ii) stabilize the yen/dollar exchange rate.

Since the 1990s, the bilateral policy pattern between the US and Japan has evolved further. After the mid 1990s, the US economy was soaring with the IT boom and an asset bubble while the Japanese economy was stagnant,. The usual US demand to open up Japan and appreciate the yen was in recess even though the Japan-US trade gap remained very large. It was thought that further destabilization of the Japanese economy would be bad for the world as well as the US economy. But now, the American bubble has burst, the fiscal problem has returned, and the Bush administration is worried about sluggish job creation.

In the last few years, some Japanese officials and economists argued for a depreciation of the yen in order to boost the weak domestic economy, since fiscal and monetary stimuli have all failed. However, if Japan and the US both want a depreciation of its own currency simultaneously (which is impossible to realize), I do not know what will happen. In reality, the dollar declined against the yen and especially the euro in 2003 and 2004. The US government continues to send very ambiguous signals as to the desirability of the dollar's depreciation.

In the mean time, China has replaced Japan as the largest trade surplus country vis-a-vis the US, and a similar trade friction has emerged between China and the US. As expected, the US now demands an appreciation of the Chinese currency (RMB) to reduce its competitiveness. China has maintained a fixed exchange rate and tight capital control, so the situation is not exactly the same as with Japan. But how to manage the RMB has now become one of the major questions in the world economy. The Chinese government hints its intention to make RMB more flexible in the future, but it does not give any details.

Earlier, Japan was the target of global criticism because it was too strong. Now, Japan is weak and does not draw much attention from foreign governments. This change is described as "Japan bashing" turning to "Japan passing." The Japanese like self-depreciation and are very sensitive to how others perceive them.

During the high growth period of the 1950s-60s, the central government budget was generally sound. It was in surplus and no government bond was issued until 1965. But in the mid to late 1970s, fiscal expansion to stimulate the economy was activated in a big way, financed by the issuance of new government bonds (mostly in 10-year maturity; later in shorter maturities also). Public debt quickly accumulated.

In the 1980s, the Japanese Ministry of Finance started an initiative for fiscal consolidation. A tighter budget and bold expenditure cuts were targeted. Fiscal and administrative reforms were proposed and partly carried out.

The Second Special Administrative Reform Study (Dai Ni Rincho, 1981-83), an official advisory organ headed by former Keidanren President Toshio Doko, recommended expenditure cuts without a tax increase for fiscal consolidation. His recommendations also included more international contribution through increased ODA and military spending, reduction of healthcare costs, and private-sector initiative. Mr. Doko himself was a man of self-discipline and meager living. He ate a small dried fish for breakfast.

The Maekawa Report (1986-87), prepared by a private advisory group to prime minister Nakasone (headed by the former Bank of Japan Governor Haruo Maekawa), recommended expansionary fiscal and monetary policy to boost domestic demand, economic deregulation, and reduction of the trade surplus to avoid friction with the US. His low interest rate policy was later criticized as causing an asset bubble. Also, Prof. Ryutaro Komiya severely criticized Mr. Maekawa's recommendation for trade surplus reduction, saying that the surplus was a macroeconomic variable and should be left to the market (see below).

Thanks to the effort of the Ministry of Finance and the asset bubble in the late 1980s, the fiscal balance gradually improved in the late 1980s. But the bubble burst in 1990-91 and the Japanese economy plunged into a long recession. Fiscal stimuli were tried in increasingly large amounts in the 1990s and public debt began to accumulate again.

Prof. Komiya and the Japan-US trade friction

His main research area is international economics. In addition to theoretical works, Prof. Komiya has written many books criticizing the policies of the Bank of Japan and the Japanese and US governments. In his 1994 book (see the reference list), he flatly dismissed the idea that Japan's trade surplus was due to the closed nature of Japanese markets. He argued that the trade gap was fundamentally a macroeconomic phenomenon of the savings-investment balance. Unless the US adopted internal policies to increase its own saving rate, Komiya said that no trade negotiation or exchange rate manipulation would "resolve" the trade gap issue. He also criticized the Maekawa Report as completely misguided. Here are some excerpts from his book:

|

<References>

Komiya, Ryutaro, Boeki Kuroji Akaji no Keizaigaku: Nichibei Masatsu no Orokasa (Economics of Trade Surplus and Deficit: The Folly of the Japan-US Friction), Toyo Keizai Shimposha, 1994.

Kosai, Yutaka, En no Sengoshi (The Postwar History of the Yen), NHK Ningendaigaku Textbook, 1995.

McKinnon, Ronald I., and Kenichi Ohno, Dollar and Yen: Resolving Economic Conflict between the United States and Japan, MIT Press, 1997. Also available in Japanese translation (Toyo Keizai 1998).