9. The 1930s and War Economy

(See Handout no.7)

Showa Depression 1930-1932

Japan experienced the deepest economic downturn in modern history during

1930-32. This should not be confused with the banking crisis of 1927 (previous

lecture).

There were two causes of this depression.

(1) Internally, the Minsei Party government (July 1929-April 1931, with prime

minister Osachi Hamaguchi, finance minister Junnosuke Inoue, and foreign minister Kijuro Shidehara) deliberately adopted a deflationary policy in

order to eliminate weak banks and firms and to prepare the nation for the return to

the prewar gold parity (fixed exchange rate with real appreciation). The policy of deflation and

return to gold was strongly advocated and implemented by finance minister

Inoue.(2) Externally, Black Thursday (Wall Street crash) of October 1929 and the

ensuing Great Depression in the world economy had a severe negative impact

on the Japanese economy.

Its main consequences on the Japanese economy and society were as follows:

--As before, macroeconomic downturn was felt primarily in falling prices and

not so much in output contraction (estimated real

growth was positive during this period). As prices fell, manufacturers

produced even more to maintain earning and keep factories running. But

clearly, this behavior would collectively

accelerate the oversupply and the deflation. From 1929 to 1931, WPI fell about

30%, agricultural prices fell 40%, and textile prices fell nearly 50%.

|

|

The famous photo of hungry children

eating white radish [however, they do not appear on the

verge of starvation to me. I think there were worse situations than

this in the world]. |

--Around 1931, rural impoverishment became severe. Moreover in 1934, rural

communities were hit by famine. Especially in Tohoku (northeastern)

Region of Japan, rural poverty generated many undernourished children and

some farmers were forced to sell their daughters for prostitution. This

rural disaster caused much anger and popular criticism against the government and big

businesses.

--Cartelization and rationalization were promoted under government guidance.

Free market seemed to worsen the depression, so agreements on output

restriction were adopted. This practice spread to virtually all material

industries including cotton yarn, rayon, carbide, paper, cement, sugar, steel,

beer, coal and so on.

--Military and right-wing movements emerged. In economic despair, much blame

was placed on party governments and their policies. Even ordinary people,

who normally hated militarism, were disappointed with the performance of party

governments and became more sympathetic to the military and nationalists.

In the 1930s, political and intellectual thinking gradually shifted from

economic liberalism toward more economic control under state management.

There were many reasons for this, including: (i) influence of Marxism; (ii)

apparent success of USSR; (iii) Showa Depression; (iv) the idea that deflation

was worsened by excess competition; and (v) disappointment with politicians and

political parties. Many considered that the days of the US-style free market economy

were over and from now on, state control and industrial monopoly would

strengthen the competitiveness of the national economy.

Another aim of the military and right-wing groups was active military

expansion. They criticized "Shidehara Diplomacy" which to them seemed too

soft on China. Their primary goal was to "defend Japanese interests in

Manchuria and Mongolia [more precisely, eastern part of "Inner" Mongolia]).

Seiyukai versus Minsei Party

Seiyukai (full name: Rikken Seiyukai) was established in 1900 by the union of

a leading politician (Hirobumi Ito) and a former opposition party who decided to cooperate with the government. Its main policies were (i) fiscal

activism with an emphasis on public investment in rural and industrial

infrastructure; (ii) acceptance of military buildup and expansion; and (iii) pleasing a narrow

voter base (rural landlords and urban rich). It was a party supportive of a big government allocating public money and subsidies. Seiyukai

literally means "political friend

society."

Minsei Party (full name: Rikken Minsei To) was originally called Kenseikai

(1916-), later merged with another party to become Minsei Party in 1927. Its

main policies were (i) economic austerity and industrial streamlining (free

economy and small

government); (ii) return to prewar gold parity; and (iii)

international cooperation and peaceful diplomacy especially with the US. Its

support base consisted of intellectuals and urban population. Minsei means

"people's politics."

| |

Minsei Party |

Seiyukai |

| Main supporters |

Intellectuals, urban workers |

Big businesses, rural landlords |

| Economic policy |

Small government, free market principle, eliminate

inefficient units through macroeconomic austerity |

Big government, fiscal activism, public investment for

industry and rural development |

| Foreign policy |

Cooperate with US, oppose military invasion of China

(protect Japanese interests through diplomacy) |

Supporting military expansion, cooperate with

military, if necessary, to undermine Minsei Party |

| Finance minister & economic policy in the 1930s |

<Junnosuke Inoue, until Dec. 1931>

Intentionally generate deflation

Return to prewar gold parity

|

<Korekiyo Takahashi, Dec. 1931-Feb. 1936>

End gold parity and depreciate yen

Fiscal expansion (later, tight budget)

Easy money |

Japanese voters did not always vote for the same party but often switched

their support from one party to another depending on the issue and situation.

Smaller "proletariat parties" also emerged with farmers and workers as

the

support base.

As noted earlier, Junnosuke Inoue of Minsei Party (finance minister 1929-31) was deeply

committed to the policy of deflation and returning to gold. This policy caused severe depression

but he never relented or regretted. People became greatly frustrated with his policy.

Finally, the government (second Wakatsuki Cabinet) was removed and succeeded by

a Seiyukai government (Inukai Cabinet) in December 13, 1931.

As soon as the new Seiyukai government was sworn in, finance minister

Korekiyo Takahashi completely reversed Inoue's policies:

--On the very first day of the new government, Takahashi ended the gold

standard and the fixed exchange rate, and floated the yen. It immediately

depreciated.

--Fiscal expansion financed by government bond issues (called "Spending

Policy"). Monetization of fiscal deficit was tried for the first time

in Japanese history (BOJ buys up newly-issued government bonds).

--Monetary expansion and low interest rates.

Thanks to this policy turnaround, the Japanese economy began to recover in

1932 and expanded relatively strongly until 1936 (the last year of non-wartime

economy). Among major countries, Japan was the first to overcome the global

depression of the 1930s. Fiscal and monetary expansion seemed appropriate. But

the yen's large depreciation might be considered as the

"beggar-thy-neighbor" policy (i.e., a cheaper yen was beneficial to

Japanese industries but it imposed costs on other countries through real

appreciation of their currencies).

For these achievements, Korekiyo Takahashi is called "Japanese

Keynes." He adopted Keynesian policies even before John Maynard Keynes wrote the

famous General

Theory in 1936 ! Even today, Takahashi's policy is admired while Inoue's policy

is generally criticized as stubborn and misguided. But this view is sometimes

challenged and continues to be debated. As recently as in 2001, Prof. Junji Banno (Chiba

University) wrote that Inoue's deflation policy was pre-requisite for economic expansion of the

mid 1930s, because without it efficiency improvement could not have been

achieved. His article indirectly criticizes the current Koizumi government's policy

of supporting weak firms and banks without painful restructuring (see the box at

the end of lecture

8).

|

|

|

|

| Junnosuke Inoue,

1869-1932 (Minsei Party); also see Lec.7 |

Osachi Hamaguchi,

1870-1931 (Minsei Party)

His policy |

Tsuyoshi Inukai,

1855-1932 (Seiyukai) |

Korekiyo Takahashi

(Japanese Keynes?), 1854-1936 (Seiyukai) |

Around 1934 when the Japanese economy was firmly on a path to recovery, Takahashi shifted to

a tighter budget (which seemed an appropriate decision). But the army and navy demanded more

military spending despite fiscal pressure. Takahashi resisted and was

assassinated by a military group in the February 26 Incident in 1936 (next section).

Both Inoue and Takahashi previously served as a Bank of Japan governor before

becoming a finance minister, but

their personalities differed significantly. Inoue was a slim, intellectual graduate from Tokyo University. Takahashi was fat and extremely popular

among people (his nickname was "Daruma," a round doll). He did not

have much education and had a rough life when he was young.

Political terrorism and invasion of China

From 1931 to 1937, Japanese politics was gradually overtaken by the military.

Many incidents occurred, each undermining the basis of party government. Within

the army and navy (especially the army), a few ultra-nationalist groups formed

with the

purposes of rejecting a party-based political system, uniting the nation under

the emperor,

introducing economic planning, saving the rural poor, and so on. They staged many

coups and assassinations. Below is the brief history of this dismal period. Underlined incidents were particularly

significant.

| 1931 |

March Incident (failed military coup attempt). |

| Manchurian Incident (Sept. 18 Incident)--a few officers

of Kantogun (Japanese army stationed in China), including Kanji

Ishihara and Seishiro Itagaki, started military invasion by exploding a

railroad track and blaming it on Chinese. Ishihara's idea was that Japan had

to take Manchuria (Northeastern China) in order to prepare for a full war against the

US. They started the incident without informing the Tokyo government or

army headquarters. Foreign minister Shidehara told Kantogun to

refrain from further military action but Ishihara's group ignored the order. The

Chinese side adopted non-resistance strategy, and Manchuria was soon occupied by

the Japanese troops. This incident clearly showed

that the party government could no longer restrain the behavior of the military.

|

| October Incident (failed military coup attempt). |

| 1932 |

Blood Society Incident--Junnosuke Inoue (former finance minister) and

Takuma Dan (Mitsui Group) were assassinated. |

| Establishment of the state of Manchuria (Japanese puppet

state). |

| May 15 Incident--navy officers assassinated prime minister Tsuyoshi

Inukai (Seiyukai). |

| 1933 |

Japan was criticized by the League of Nations over the

occupation of Manchuria. In protest, Japan withdrew from the League of

Nations. |

| The period 1933-35 was relatively "quiet" thanks to economic

recovery and fewer domestic and international incidents. But this

proved to be a temporary calm before the big storm. |

|

1936 |

February 26 Incident--nationalistic army officers led their troops

to stage a military coup on a snowy morning in Tokyo. They wanted to get rid

of the current government and start a new regime. Korekiyo Takahashi

(finance minister), Makoto Saito (interior minister) and Jotaro Watanabe

(education minister) were assassinated. The coup group occupied central

Tokyo for four days. The army headquarters first approved their action but

later disowned them, because Emperor Showa angrily told the military to put

down the rebellion. The coup thus failed, but after this incident the party

government was marginalized and the military controlled Japanese

politics. |

| During all these incidents, Seiyukai behaved opportunistically, often supporting the

military in order to politically attack its rival, Minsei Party. It was a risky tactic

since the goal of the military was to remove all political parties including

Seiyukai ! (By contrast, Minsei Party more consistently opposed the

military.) Political parties were seriously discredited in the eyes of the

public due to (i) inability to oppose the military, (ii) money politics and corruption, and

(iii) Seiyukai's self-destructive move to cooperate with the military. |

|

1937 |

Japan-China War began--on July 7, Japanese and Chinese troops had a

skirmish at Marco Polo Bridge near Beijing (Beiping). The incident was minor but Tokyo

(Konoe Cabinet) decided to send more troops to China. Thus began a

full-scale war with China (until 1945). |

After the Japan-China war erupted, political parties were emasculated and

later disbanded, the military completely took over Japanese politics, and the entire nation was mobilized to execute the war.

In my view, Japan crossed the point of no return with the Manchurian

invasion in 1931. With this incident, Shidehara Diplomacy ended and the

military's influence surged. International isolation became unavoidable. Party

governments were too weak to stop this trend. While some factions within

Seiyukai and Minsei Party tried a few times to merge the two parties to oppose

militarism, their attempt did not materialize. Starting with the Manchurian

Incident, the period 1931-1945 is sometimes called the "Fifteen-Year War."

|

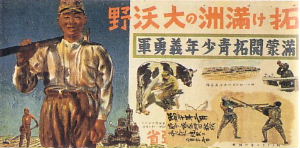

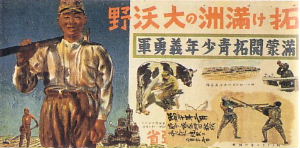

The head office of the South

Manchuria Railway controlled by Japan (left) and its poster (below). |

|

|

|

The poster says "Open up

the fertile land of Manchuria: Young Volunteer Army for Cultivating

Manchuria and Mongolia" |

War economy, 1937-1945

The military leaders thought (hoped) the war with China would be short. But in reality, it lasted

for eight years. Without realistic vision or planning, the war front expanded and

fighting escalated. Within China, the nationalists and the communists were fighting each other

at first but later joined forces to fight the Japanese.

While there were earlier calls for economic planning before the war, the Japanese

economy basically remained market-oriented until 1936. But with the outbreak of

the Japan-China War in 1937, the economy was completely transformed for war

execution. One by one, new measures were introduced to control and mobilize

people, enterprises and resources. Most Japanese firms remained privately-owned

but were heavily regulated to contribute to the war effort.

Key measures for establishing the war economy included the following:

1937--The Planning Board (kikakuin) was created. This board, directly

under the prime minister, was responsible for comprehensive policy design for

wartime national resource mobilization. The brightest bureaucrats from

various ministries

were gathered for this purpose. It basically played the same role as the

state planning committee in socialist countries.1938--The Planning Board issued the Resource Mobilization Plan (first

economic plan). Separately, the National Mobilization Law was approved.

1940--Konoe Cabinet's New Regime Movement. This movement was started in response to

Japanese invasion of Southeast Asia and German victories in Europe. A strong

one-party system was advocated and adopted. Existing political parties were

dismantled.

1943--The Military Needs Company Act was adopted. Designated companies were

placed under official control (top management, production plan, penalty for

non-compliance, etc) but at the same time they were provided with necessary inputs on

a priority basis.

In addition, rationing, forced enterprise mergers, and forced factory labor were

adopted in increasing intensity.

For economic planners, the primary objective was to maximize military

production under limited domestic resources and availability of imports. Key military

products were ships and warplanes. Toward the end of the war, airplane production became

the only priority. In order to boost heavy industries, consumption was greatly

squeezed and light industries were suppressed. The textile industry (previously

the leading industry of Japan) was virtually eliminated. The people were forced

to live without a new supply of clothes and footwear. Steel products in

structures and households were stripped as the metal source for building more

airplanes and ships.

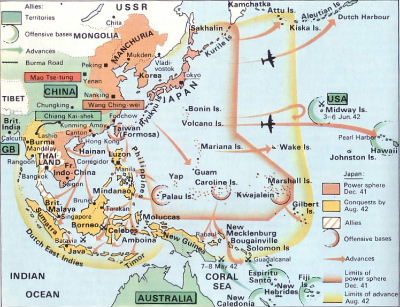

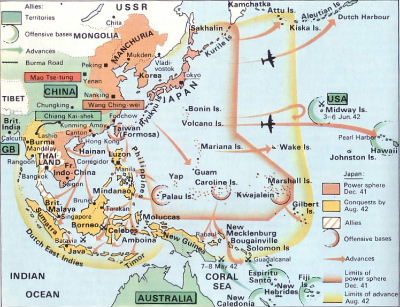

|

|

RED (Dec.1941): Japan's occupied areas

immediately after the Pacific War started. YELLOW (Aug.1942): Japan's maximum military

expansion. After this, Japan began to retreat. |

In wartime planning, two variables were crucial: (i) foreign exchange reserves; and (ii) energy and

raw materials (and the capability to transport them by sea). Until around 1940, the question

was how to maximize military output subject to these two constraints. But after

1940, Japan could no longer trade with other countries and the problem shifted

to the physical transportation of natural resources from the Japanese colonies and

occupied areas to mainland Japan.

Japan considered that resources from the "Yen Bloc"

(Korea, Taiwan, Manchuria and the rest of occupied China) were not enough. In July

1941, in order to secure more resources, Japan began to invade Southeast Asia, starting

with French Indochina (Vietnam). This angered the US, which imposed oil embargo

and asset freeze on Japan. If oil imports from the US were cut off, Japan's oil

reserve would last only two years. At this point, Japan began to prepare a war

with the US. Diplomatic efforts to maintain peace were tried but failed. With

the Pearl Harbor attack in December 1941, Japan started the Pacific War against the

US and its allies.

Japanese leaders did not have any clear idea regarding how to fight a war against the

US, let alone how to win it. However, they were encouraged by the brilliant

victories of Nazi Germany in Europe. To them, totalitarianism of Japan, Germany and the USSR

seemed superior to American capitalism and individualism.

Immediately after the outbreak of the Pacific War, Japan invaded a wide area of Southeast Asia but soon began to retreat

under allied counter-attacks. Japanese ships and planes were quickly lost while

Americans built more and more of them. From late 1944, US aerial bombing (mainly

incendiary bombs) destroyed virtually all cities in Japan (except Kyoto). In

1945, the US troops landed in Okinawa, two atomic bombs were dropped in Hiroshima

and Nagasaki, and the USSR entered a war against Japan. A few days later, Japan

surrendered.

Economically, the main reason for Japan's defeat was that its war

economy collapsed due to the lack of inputs and energy. Japan lost virtually all

ships and could not transport materials from abroad (including colonies).

|

|

|

Neighborhood groups were organized

to put off fire from US bombing. Actually, the bombing was so

fierce that this kind of exercise was virtually of no use. |

As young males were sent to war

fronts, women were trained to defend the homeland. Due to the lack of

weapons, they were provided with bamboo swords. Women and high school

students were also mobilized to work in military factories. |

The

origin of the Japanese system

Many of the characteristics of the post-WW2 Japanese economy originated

during the war period

(1937-1945). They feature long-term relationship and official intervention

such as:

Heavy and chemical industrialization drive

Administrative guidance (gyosei shido)

Subcontracting system

Separation of ownership and management

Lifetime employment system and seniority wage

Enterprise-based trade unions

Financial keiretsu and mainbank system

The Bank of Japan's "window guidance" and "convoy system"

Food control system

Foreign exchange budget and surrender requirement

All of these policies and systems were deliberately adopted by the government

in the late 1930s through the early 1940s in order to effectively execute the war. Before that,

the Japanese economy was more neoclassical-- characterized by freer entry,

short-term contracts and high labor mobility.

These wartime features were largely retained even after WW2 and worked

relatively well in the 1950s and 60s when Japan was growing rapidly. However, they are now considered

obsolete and to have become barriers to change in the age of IT and

globalization. Among the list above, the last one was abolished long ago but most others still remain

in the Japanese economy even today in various degrees.

There is a debate among economists regarding the interpretation of

the Japanese system.

The majority of Japanese economists argue that Japan should go back to the free market

model, because the relational and interventionist system was originally alien to

Japan. These may have played a historical role before, but we do not need them

any more (some aspects, like priority on job security, could be partially

retained, however). Prof. Masahiro Okuno-Fujiwara and Prof. Tetsuji Okazaki (both

at Tokyo University) are leading advocates of this view.

But a minority voice says that Japan needed a system based on long-term

relations, with or without

war. When an economy graduates from the light industry stage (textile, food

processing, etc) and

moves to heavy industrialization and machinery production, free markets may not be the best choice. Official support

and long-term relationship become indispensable for industries with large

initial investments, high technology and intra-firm labor market. As Japan began heavy

industrialization in the 1920s and 1930s, the free economic system inherited

from Meiji was inappropriate and had to change. The war provided a good excuse for

this change. But even without the war, Japan had to adopt a new system anyway. Prof. Yonosuke Hara (Tokyo University) presents such a view. He says that the free economy

of Meiji was foreign, and the relational and interventionist system is more normal

to Japan, dating back to the Edo period.

According to the latter view, implications for today's developing countries are as follows. Light industries

and electronics assembly can be

promoted by free trade and FDI, but if the country hopes to absorb technology

vigorously and have advanced

manufacturing capability, certain industrial promotion measures become

necessary; Japan, Taiwan and Korea all adopted this method in the past. By

contrast, no ASEAN countries seem to have broken through this "glass ceiling"

and internalized the industrial power. If

latecomer countries are now banned from taking these measures because of WTO,

FTAs, World Bank policy matrix and so on, they may remain

at a low level of industrialization (contract manufacturing, simple processing, etc) and not get to

a higher level of technology.

|

<References>

Banno, Junji, Nihon Seijishi: Meiji, Taisho,

Senzen Showa (History of Japanese Politics: Meiji, Taisho and Prewar Showa),

University of the Air Press, revised 1993.

Iwanami Shoten, Nijukozo, Nihon Keizaishi 6 (The Dual Structure, Japanese Economic History vol.

6), T. Nakamura and K. Odaka, eds, 1989.

Iwanami Shoten,

Keikakuka to Minshuka, Nihon Keizaishi 7 (Planning and

Democratization, Japanese Economic History vol. 7), T. Nakamura ed, 1989.

Noguchi,

Yukio, 1940 Nen Taisei: Saraba Senji Keizai (The 1940 Regime: Goodbye to

the War Economy), Toyo Keizai Shimposha, 1995.

Okazaki,

Tetsuji, and Masahiro Okuno, eds, Gendai Nihon Keizai System no Genryu (The

Source of the Modern Japanese Economic System), Nihon Keizai Shimbunsha, 1993.

Takafusa Nakamura, Showa Kyoko to Keizai Seisaku (Showa Depression and

Economic Policy), Kodansha Gakujutsu Bunko, 1994.