(See handout no.9; chapter 12)

In the developing world, there were severe financial crises in both the 1980s and 90s. But the nature of crises was quite different between the two decades.

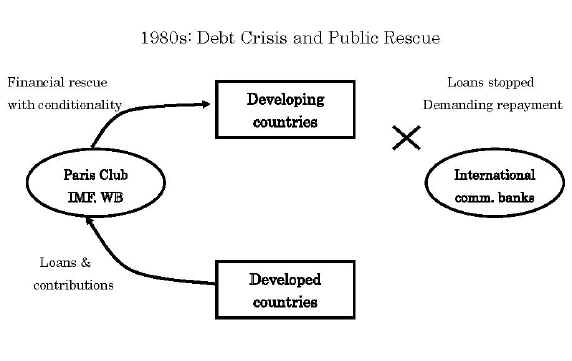

In the 1980s, the world experienced a debt crisis in which highly indebted Latin America and other developing regions were unable to repay the debt, asking for help. The problem exploded in August 1982 as Mexico declared inability to service its international debt, and the similar problem quickly spread to the rest of the world. To counter this, macroeconomic tightening and "structural adjustment" (liberalization and privatization) were administered, often through the conditionality of the IMF and the World Bank. This crisis involved long-term commercial bank debt which was accumulated in the public sector (including debt owed by SOEs and guaranteed by the government). The governments of developing countries were unable to repay the debt, so financial rescue operations became necessary.

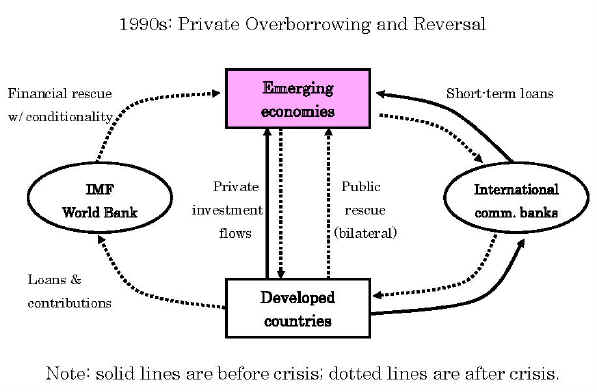

By contrast, the 1990s crises were more staggered and sequential (not happening at the same time). We had the Mexican crisis in 1994, the Asian crisis in 1997, the Russian crisis in 1998, the Brazilian crisis in 1999, the Argentine crisis in 2002, etc. [In addition, we had big EMS currency crises in Europe in 1992 and 1993 but their characteristics were different.] These crises were often caused by short-term commercial bank debt and/or securities market investment. Particularly in the case of the Asian crisis, the private sector (not the public sector) was the main culprit. Banks, nonbanks and corporations overborrowed, and foreign banks and private investors overlent. Huge capital outflows and severe currency speculation often accompany these crises.

In both cases, Mexico had the honor of starting a new type of financial crisis.

Generally speaking, instruments of external development finance (other than FDI) can be classified as follows:

(1) Official grants and loans (often concessional--i.e., at low interest rates and with grace periods and long maturities)

(2a) Long-term commercial bank loans

(2b) Short-term commercial bank loans

(3) Securities markets (bonds, equity)

This list is in the ascending order of instability. ODA flows are more stable and predictable (unless you have a problem with big donors or international organizations) while securities markets can be very volatile. In the latter case, it is almost impossible even to identify who are the investors.

The 1980s crisis was caused by (1) and (2a), especially the latter. The 1990s crises were more often caused by (2b) and (3). The Asian crisis of 1997-98 was mainly caused by (2b). This however does not mean that all financial crises in the 1990s and 2000s are of the latter type. The old type crises (caused by fiscal deficits) still occur today.

When we discuss debt problems, we often hear these terms. There are two types of inability to repay.

Insolvency means the borrower (or the borrowing country) is unable to pay back, both today and in the future. It has spent money beyond its inter-temporal budget constraint, so there is no way they can service the debt in full, even if they try. In this case, waiting does not improve the situation. The lenders must face the inevitable result that some (or even all) of the money will not be repaid. The only solution is forgiving debt--give up the hope of full repayment.

Illiquidity means the borrower (or the borrowing country) is unable to pay back now, but it can pay back later. It just does not have enough cash in the pocket (or not enough international reserves in the central bank), but it expects future income or export receipts so debt will be fully serviced (with added interest for late payment) in the future. In this case, the appropriate response is delaying the repayment, or "debt rescheduling."

Thus, the policy response should be very different depending on whether the country is facing a solvency problem or a liquidity problem. The first is more serious than the second.

But this is a theoretical distinction. The big problem is: it is very difficult to distinguish the two cases in reality. When a crisis happens, it is virtually impossible to tell precisely whether Russia, Argentina, Thailand, or any other country has a solvency problem or a liquidity problem, especially ex ante (before the event) but even ex post (after the event).

A similar situation can occur with the concept of sustainability of the balance of payments. When a developing country is accumulating foreign debt (whether ODA or commercial), how can we tell whether it will repay the debt in the future? It depends on many factors: (i) whether industrialization succeeds; (ii) whether political stability is maintained; (iii) whether the global business condition is favorable; (iv) whether export and import prices rise or fall; (v) whether world interest rates rise or fall; (vi) whether regional crisis, war, terrorism, etc. occurs, ... We can calculate the balance-of-payments viability with a simple model with rigorous assumptions. But for practical purposes, sustainability is highly uncertain. For example, there is no easy way to predict whether or not a country succeeds in development in the long run.

There are more complications.

There are cases where the country wants to repay, but cannot (inability). There are also cases where the country can repay, but will not (unwillingness). Again, it is sometimes difficult to tell them apart.

Furthermore, insolvency or illiquidity may be the outcome of wrong policy. If the government implements wrong measures, the problem can worsen from illiquidity to insolvency. It is also possible that international organizations impose wrong policy conditionality so the situation deteriorates.

When we consider the debt crisis in the 1980s and the currency crises in the 1990s, an interesting comparison can be made between Latin America and East Asia. While both regions were affected by these crises, Latin America was more severely impacted by the 1980s crisis while East Asia was more directly hit by the 1990s crisis.

After the Asian crisis of 1997-98, some people argued that the high growth of East Asia was now over, the Asian development model was no longer useful, and Asia would have hard time growing in the early 21st century. It is true that some Asian economies (for example, Japan, the Philippines and Indonesia) struggled economically and/or politically in the aftermath of the crisis. But we also see strong growth dynamism too (for example, China, Vietnam and Thailand). It is a bit of exaggeration to say that the Asian crisis permanently and significantly reduced the growth prospects of the region. I think East Asia is still dynamic, even with many problems.

In the long-term perspective, it is undeniable that East Asia as a region has succeeded in sustaining growth and improving living standards. This is in sharp contrast to the Latin American experience where consistent growth has been highly elusive. In the 19th century, Argentina was one of the "developed" countries with relatively high income. But since then, its development path has been strewn with many instabilities. Even in the early 21st century, it remains a developing country saddled with gigantic economic problems.

But if we take a long-run view and compare East Asia and Latin America, it is hardly deniable that East Asia on the whole has succeeded more brilliantly in economic development. Many economies in East Asia (but not all of them--at least not yet) have raised income significantly and promoted industrialization after political independence, and especially during the last few decades. The question is WHY?

(Some say that Chile is really an East Asian country, with its authoritarian past, disciplined policies and successful export promotion; and the Philippines belongs to Latin America with its social conflicts, political instability and low growth.)

Each country in East Asia is different, and each country in Latin America is also unique. Therefore, generalization is not easy. But at the risk of oversimplification, we can list some of the typical characteristics of these regions which affect their long-term development performance.

First and perhaps most important, inequality (between rich and poor, cities and country side, white and non-white, etc) has remained and even intensified in Latin America over the centuries. There seems to be a socially ingrained mechanism to reinforce these social divisions in Latin America which continue even today. In contrast, in most of the successful East Asian countries, social divisions as initial conditions were less severe, governments have made effort to narrow income gaps and unite different social groups, and growth (accompanied by appropriate policies) generally reduced these gaps.

Second, generally speaking, Latin America is more resource-rich while East Asia is less so (they are people-rich). As we discussed in lecture 8, a large endowment of natural resources is often an impediment, rather than a help, to industrialization. One reason is economic: the "Dutch Disease," or exchange rate overvaluation and crowding out of limited domestic factors of production by the extractive sector, suppresses the growth of other tradable industries. Another reason which is important in Latin America is political: natural resources tend to create strong vested interest groups around them (rich commercial farmers and landlords, mining interests, etc). They favor overvaluation and free trade, and oppose public investment for industrial growth. Because of their resistance, industrial promotion policy is more difficult to implement in such countries. This problem was largely nonexistent in East Asia.

Third, there was a difference in political regime. Latin America had "soft" states while East Asia had "hard" states. For a long time, politics in Latin America was characterized by instability and oscillation between militarism and populism (but now, almost all Latin American countries are democratized). Populism is a political system supported by many interest groups. The government must please these groups continuously and simultaneously. Stability is maintained through delicate political balancing acts. Wealth must be distributed among these supporters. This prevents taking decisive action and making quick response. On the contrary, East Asia typically had a top-down, non-democratic authoritarian state as it initiated industrialization. Such a government is very strong and does not have to appeal to various interest groups. If the leader is intelligent and farsighted (a big "if"), it can have very agile and dynamic policies. Some countries in East Asia still have such a regime.

Other differences include the social continuity after colonization (original societies in Latin America were destroyed by the whites, while Asian societies survived colonization) and growth strategy (import substitution was continued longer and in a more counter-productive manner in Latin America).

------------------------------------------------------

The standard explanation of why the debt crisis occurred in the 1980s goes something like the following. We must first look at the 1970s for the background and then see what happened in the 1980s. Between these two decades, the financial flows surrounding developing countries changed dramatically.

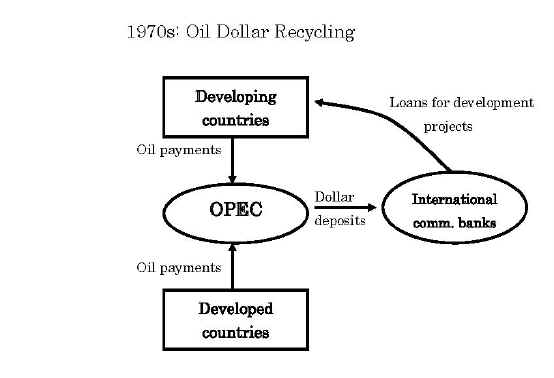

The 1970s was an inflationary decade. In particular, there were two "oil shocks" in which the world oil price was greatly increased due to political and military reasons, in 1973-74 and 1979-80. As a result, huge oil export earnings flowed into the OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries). At the same time, non-oil producing developing countries suffered from ballooning trade deficits. As the graph below shows, the real price of oil peaked around 1980. Although the nominal oil price is accelerating in recent years, its inflation-adjusted level is currently not as high as in 1980.

Real Oil Price

(WTI in constant USD of July 2005)

Sources: National Post with data from Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The world's purchasing power accumulated in OPEC but they had little absorptive capacity. This means that they could not immediately invest the money in domestic industrial projects. Their export earnings were deposited at banks for the moment. The OPEC countries typically deposited their oil receipts in dollar accounts located outside the US (remember, oil receipts are in US dollars). These were called "euro" dollar deposits. How to mobilize this huge euro-dollar deposits for global growth became a big financial problem of the 1970s. This was called the problem of "oil dollar recycling" (American English) or "petrodollar recycling" (British English).

Here, the adjective "euro" means outside the original issuing country. For example, US dollar deposits outside the US (say, in London) are called "euro-dollar deposits." Japanese yen bonds issued in New York is called "euro-yen bonds," and so on. This term has no direct relation to geographical Europe. The point is, in those days, "euro" transactions were freer because they were outside the country which wanted to regulate them. But as financial liberalization proceeded, even the original country dropped regulation and added convenience of euro-money was gradually lost. Today, this terminology has become obsolete and is used only in the historical context. Virtually everyone thinks the euro is the currency unit of Europe, not an adjective.

Large international commercial banks which received the OPEC money decided to reinvest it in developing countries with good growth prospects. Usually, a group of such banks got together and lent money to a developing country endowed with a lot of primary commodity resources or "good" industrial projects (Brazil, Mexico, Korea, Indonesia, etc). Such group lending by banks is called "syndicated loans." These were long-term commercial bank loans to the governments of developing countries (or to SOEs with government guarantee). With ever-rising commodity prices, these investments looked very safe and profitable.

Some of the developing countries were also very aggressive in receiving such loans to promote national development projects. They were optimistic and borrowed happily. As a result, they became heavily dependent on foreign bank loans.

However, not all developing countries enjoyed foreign loans and investment booms. Some non-oil producing developing countries as well as industrial countries in North America, Europe and Japan were experiencing "stagflation"--a situation of high inflation and stagnant output.

|

|

Paul Volcker (1927-), Fed chairman 1979-87. |

But good times do not last forever. As the new decade of the 1980s began, the global economy shifted dramatically from inflation to recession.

In late 1979, Mr. Paul Volcker was appointed as a new chairman of the US Federal Reserve Board (i.e., American central bank). Immediately, he initiated an anti-inflation campaign. From 1979 to 1980, the Fed tightened money supply. As a result, dollar interest rates shot up sharply, even to 20% per year or above. Although this caused serious economic slowdown in the US and the rest of the world, in the long run Mr. Volcker succeeded in stopping the global inflation of the 1970s. But this process caused enormous strain for highly indebted developing countries.

The tightening of American monetary policy impacted indebted countries in three ways:

--As dollar interest rates rose, debt service payments also rose sharply.

--Due to global recession, the quantitative demand for their exports fell.

--As commodity prices declined, they faced lower "terms of trade" (= export price/import price)

Thus, highly indebted countries suddenly faced payment difficulties. Finally, in August 1982, Mexico said, "Sorry, we can't service our debt any more." This ignited a global crisis. It was not just Mexico that had the balance of payments problem. One by one, debtor countries declared similar inability to repay.

I was a summer intern at the IMF's Western Hemisphere Department in 1982. As the Mexican problem erupted, the Mexican division of IMF became empty. I was assigned to East Caribbean Division where it was less exciting but more peaceful. I was asked to calculate real effective exchange rates for East Caribbean islands. In those days, computers looked much like vacuum cleaners.

As soon as the debt crisis broke out, foreign commercial banks stopped lending to them, and began to think only of getting the money back. The oil dollar recycling and syndicated loans were completely terminated. After this, the financial rescue was extended to them by the IMF and the World Bank in close collaboration with the US government. They extended loans to fill the "financing gap," provided that the government of the affected country took the "correct" adjustment policies. Ultimately, these official loans were financed by developed countries through capital contributions and loans.

Sometimes the amount of financial help needed was so huge that IMF and World Bank loans were not enough. The international community provided larger loans through the Paris Club, a group of official lenders to a particular developing country, which rescheduled existing debt or provided new money in exchange for full servicing of the existing debt. (Technically, rescheduling means delaying the payment of old debt and new money means extending new loans if old debt is repaid as scheduled. But economically, they have the same balance-of-payments impact). The Paris Club rescheduling (or new money) was conditional on the existence of an IMF agreement. Bilateral official lenders extended rescue loans only when the IMF itself had successfully negotiated a new adjustment program (IMF loan with conditionality) with the country in question. Hence the enormous power of the IMF vis-à-vis countries in balance-of-payments trouble.

In addition, commercial bank lenders also negotiated debt rescheduling through the London Club. While the Paris Club was always held in Paris (French MOF), the London Club was not necessarily convened in London.

When providing a balance-of-payments rescue package, the IMF and the World Bank always require that appropriate corrective policies be undertaken (called conditionality). They provided the carrot and the stick.

In order to cope with the 1980s debt crisis, these international organizations created new lending facilities such as:

--World Bank's structural adjustment lending including "structural adjustment loan (SAL)," at commercial interest rate, and "structural adjustment credit (SAC)," at concessional interest rate--IMF's structural adjustment facility (SAF) and enhanced structural adjustment facility (ESAF)

Conditionality typically consisted of macroeconomic tightening (budget cuts and low credit growth to reduce domestic expenditure, i.e., "absorption") and "structural adjustment" (deregulation, privatization, trade liberalization, etc. to stimulate private supply response). The theoretical background of this strategy was called neoclassical development economics. Simply put, it assumes that the private sector will grow strongly, once macroeconomic instability and government intervention are removed.

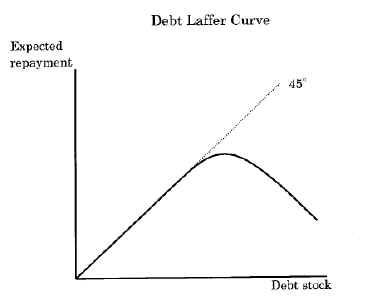

In 1985, US Treasury Secretary James Baker initiated the Baker Plan in which adjustment was combined with debt rescheduling and new money. Fifteen highly indebted countries were designated as candidates. This plan was based on the assumption that the problem was illiquidity so delaying the repayment will solve the problem. The debt stock was not reduced but the repayment schedule was simply pushed back into the future.

But when the delayed repayment approached, it was clear that the indebted countries could not pay back and the balance-of-payments situation was even worse than before. The problem was not illiquidity but insolvency. It was gradually recognized that the real solution must come from cutting the debt stock itself, not just from delaying the repayment.

Therefore, in 1989 another US Treasury Secretary Nicholas Brady launched the Brady Plan, in which market-based debt reduction was implemented. This meant that the indebted countries engaged in buying up their own debt at discount in the secondary market using various techniques (debt buyback, debt-equity swap, etc). These amounted to exchanging a large amount of your own bad debt for a smaller amount of good debt (debt you must repay in full). IMF and World Bank loans could be used for these operations. Mexico was again the first country to take advantage of this scheme [the US is always very kind to Mexico].

In addition, some countries of geopolitical importance (particularly for the US) were accorded with very generous treatment. Poland (in transition from socialism to market) and Egypt (US ally in the Gulf War against Iraq) were given debt forgiveness in which loans amounting to tens of billions of dollars were written off. They did not have to repay later or buy back their own debt--their debt was simply canceled.

One justification of such debt reduction was furnished by the Debt Laffer Curve. Originally, the Laffer Curve intended to show that as the tax rate rises, the total tax revenue of the government actually goes down beyond a certain point because people work less or try to evade taxes. This means that there is a certain tax rate that maximizes the tax revenue, and that lowering the tax rate may sometimes increase revenue (Arthur Laffer is a business professor at MIT).

Similarly, the Debt Laffer Curve shows that as the external debt stock rises, the indebted country will try to produce less (discouragement effect) or intentionally default on the existing debt (sabotage) so the foreign lenders will receive less than full repayment. Again, there is a critical debt stock beyond which both the lenders and borrowers lose. If the debt stock is already above this level, it is in the self-interest of the lenders to forgive some of the debt. But in reality, it is very difficult to tell whether a particular country has already reached this point or not.

With debt rescheduling and reduction, which were combined with neoclassical policy conditionality, the debt crisis in many countries, including those in Latin America and East Asia, were successfully contained. It took about ten years, but by the early 1990s, Latin America declared graduation from the "Lost Decade" and hoped for renewed growth. Inflation was still a bit too high in Latin America, but their economies had been liberalized and opened up externally thanks to the IMF and World Bank conditionalities, and foreign investment began to return.

The developing and transition economies which open up their financial sectors to invite foreigners to lend and invest in them are called emerging market economies. In the early to mid 1990s, this mode of attracting foreign funds became very fashionable. Many countries rushed to liberalize capital accounts (for capital mobility) as well as current accounts (for free trade) to absorb as much foreign savings as possible.

But this led to another great risk. Emerging market economies simply borrowed too much, and foreigners lent and invested too much, without much thinking and beyond sound limits. The financial sectors of these countries were still primitive. Moreover, their governments were not monitoring private-sector behavior properly. The domestic economy first enjoyed a strong investment boom and an asset market bubble, especially in land, property and stock markets. Then, the crash came. Suddenly, foreign investors and lenders pulled out in droves and the macroeconomy and the domestic currency collapsed, with the banking sector paralyzed. Enterprises were faced with bankruptcies and people suffered unemployment. Multilateral and bilateral donors had to come to the rescue after private investors left. This was the basic nature of the Asian crisis 1997-98. [Analysis of the Asian crisis will continue in the following lectures. This is only a preview.]

However, there is another part of the debt crisis story that continued beyond the 1980s. Some heavily indebted poor countries (HIPCs)--many of them in Sub Saharan Africa--could not escape from the debt trap even with repeated structural adjustment programs and debt rescheduling. Some of them went to the Paris Club for debt relief several times, or more. They continued to suffer from economic stagnation and heavy debt burden well into the 1990s. It was clear that their problem was insolvency, that their economic prospects were bleak with a huge debt overhang, and that a new approach had to be taken to stimulate development.

In 1999 at the Koln (Cologne) Summit, the HIPCs Initiative was launched. It was proposed that official debt of heavily indebted poor countries should be forgiven (including both multilateral and bilateral official loans), and the money thus saved should be used for poverty reduction.

At around the same time, World Bank President James Wolfensohn initiated the new development approach called CDF (1998) and PRSP (1999) for poor countries.

Comprehensive Development Framework (CDF) is a general philosophy and procedure under which development should take place. It emphasizes comprehensiveness, namely both economic and non-economic (i.e., social and institutional) aspects must be considered. Development must proceed with ownership (autonomy) of the developing country and partnership among all stakeholders in development. We may safely say that CDF, as a general principle, is not very operational and its political importance has already ended.Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP) is a document that spells out concrete measures and timetable (usually three years) for poverty reduction for each poor country. The allocation of tasks among various donors is also mapped out in a matrix form. Originally, only HIPC countries were required to draft this document. But now. all poor countries (i.e., all countries that receive IMF and World Bank loans on concessional terms) must produce PRSP. [In East Asia, Vietnam was the first country to draft a PRSP document, which was renamed the "Comprehensive Poverty Reduction and Growth Strategy (CPRGS)." However, the Vietnamese government decided not to do the second round of CPRGS; instead, its ideas were included in the traditional Five-Year Plan for Socio-economic Development 2006-2010.]

As of April 2006, 18 countries have reached the completion point (i.e., finished the three years of PRSP successfully). The July 2005 G8 Summit pledged full cancellation of debt owed to the International Development Association (World Bank), the IMF and the African Development Fund to countries that have reached the completion point of the Enhanced HIPC Initiative. This proposal is called the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI).

MDGs--key goals for poor countries?

Separately, the UN Millennium Summit (2000) adopted ambitious social targets to be achieved by 2015, called the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs, WB page, UNDP page), including halving the ratio of people in absolute poverty between 1990 and 2015. To attain these goals, the World Bank's PRSP is going to be used (hence the linkage between World Bank and UN policies). The World Bank economists estimated that achieving MDGs would require an additional $40-60 billion dollars of ODA per year (i.e., doubling the current level of global ODA). The EU has promised to increase its ODA to 0.39% of GNP (amounting to about $7 billion) while the US has declared to add $5 billion annually in the next three years for the benefit of poor countries with "good practice." But Japan has cut its ODA budget drastically due to fiscal crisis in recent years, and there is so far no sign that this trend will end.

Other arguments in the current global development strategy include the following:

--Some people (including NGOs and social activists) say that ODA should be given in grants, not in loans which worsens the debt burden problem.--ODA should be given to poor countries only. Middle-income countries should not receive official aid since they can attract private funds.

--ODA should be given only to poor countries with "good governance" (this is called the selectivity argument). If money is given to countries with bad policies and institutions, it will be wasted. For these countries, advice, not money, should be given.--Aid coordination and harmonization: To reduce the transaction cost (too many missions, reports, meetings, etc), aid programs must be coordinated among all donors. A common fund should be created to which all donors contribute. Sector strategies must be created and shared by all. We must avoid overlaps and duplication, since money is fungible (any contribution by any donor has the same effect [is it true?]).

However, the Japanese government has been uncomfortable with these trends, which are mostly led by Europeans. It fears too much unification of development ideas and implementation. Japan adheres to the best-mix approach which says: since the needs of each country are different and each donor has its comparative advantage, it is neither necessary nor desirable to unify all aid programs and implementation. Unnecessary procedures must be avoided, but a broad menu of alternative ideas and tools should be available to developing countries. It is up to them, not donors, to decide which goals and methods are to be adopted. Moreover, it is very risky to shift the financial management of ODA money from donors to governments (especially local governments) which are not very clean or transparent.

In summary, in the last several years, the international donor community began to respond to the debt crisis of the poorest countries by a combination of debt forgiveness and strengthened poverty reduction drive. In fact, some donors now want to use ODA for poverty reduction only (not for diplomacy, industrialization, infrastructure or competitiveness). However, whether this strategy will really work in the long run remains to be seen. Since 2002, the international organizations (especially the World Bank) has started to re-emphasize the role of economic growth and infrastructure in the process of poverty reduction. Some developing countries are tired of too much emphasis on poverty reduction and too little effort in the direction of competitiveness, industrialization and agricultural development. Clearly, this is an evolving story the end of which is still unknown to us.

<References>

Hepp, Ralf, "Can Debt Relief Buy Growth?" University of California at Davis Working Paper, Oct. 2005. paper

Khan, Mohsin S., Peter J. Montiel, and Nadeem U. Haque, eds, Macroeconomic Models for Adjustment in Developing Countries, International Monetary Fund, 1991.

Naya, S., M. Urrutia, S. Mark, and A. Fuentes, eds, Lessons in Development: A Comparative Study of Asia and Latin America, International Center for Economic Growth, 1989.

Pattillo, Catherine, Hélène Poirson, and Luca Ricci, "What Are the Channels Through Which External Debt Affects Growth?" IMF Working Paper WP/04/15, January 2004. paper

Williamson, John, ed, Latin American Adjustment: How Much Has Happened? Institute for International Economics, 1990.

For Japan's views on the current poverty reduction drive, visit the GRIPS Development Forum (English version). Especially the following papers should be useful: