Pensée Special Issue:

Special Lecture by Ban Ki-moon, Eighth Secretary-General of the United Nations

(From the March 25, 2019 edition of Pensée)

|

During his 10-year tenure as the 8th Secretary General of the United Nations, Mr. Ban Ki-moon was the chief architect of various internationally significant projects, notably the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the landmark Paris Agreement to counter climate change. He also led the Sendai Disaster Risk Reduction meeting. Mr. Ban established UN Women and guided major efforts towards the strengthening of UN peacekeeping operations, the protection of human rights, the improvement of humanitarian response, the prevention of violent extremism, and the revitalization of the disarmament agenda. Since he left office at the United Nations, Mr. Ban has assumed a number of positions of global significance, including chairman of the IOC Ethics Committee in September 2017, President of the Assembly and Chair of the Council of the Global Green Growth Institute, and Chair of the Boao Forum for Asia. |

It is a great honor and a pleasure to have this opportunity to talk about two major achievements of the United Nations, the Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Climate Change Agreement. These are the two most important achievements of the United Nations in its work towards sustainability, peace, prosperity, and human rights.

My discussion here will be practical rather than academic. I know that GRIPS students are pursuing masters and doctoral degrees, but I feel that a practical perspective will better reveal how and why the United Nations presented the Sustainable Development Goals and adopted the Paris Climate Change Agreement. These accomplishments are for the people of today, for succeeding generations, and for the planet Earth, our home.

It is impressive that at GRIPS, 60% of the students and 20% of the professors are from outside Japan. You could say that this is a miniature United Nations. I congratulate GRIPS on its vision.

The UN Sustainable Development Goals

When I was appointed UN Secretary General in 2007, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were in place, but not many people were talking about them. Six years later, there were still no advocates, and little talk about them. Achievement of the MDGs was left largely in the hands of some developing countries. I felt the situation was rather strange, and I wondered why the Millennium Development Goals were attracting so little attention.

My predecessor, Kofi Annan, had been working on the MDGs with the OECD. They really wanted to do something better, something good for humanity. That is what they were talking about with the Millennium Development Goals. The Goals had been hurriedly arranged; some scholars, politicians and economists came together for a few months, and under the leadership of the OECD, they worked hard and managed to present eight goals to the world.

We needed to really inspire people and catalyze action towards the Millennium Development Goals. But why was there so little support for the MDGs, and why was so little progress being made at that time? I began by appointing 15 world-class political leaders, scholars, and luminaries to spearhead the MDG work. From among them I asked President Paul Kagame of Rwanda and Prime Minister Luis Zapatero of Spain to lead that campaign, representing the developing and the developed countries.

When the new millennium was approaching in 1999, there was a sense of great anticipation in the world in general. Many people were talking about the Y2K computer problem, but not many people were talking about what would have to be done to improve the wel- fare of the people. At that time, hundreds of millions of people were starving to death each year. Many children died before they reached the age of five. Many women died in childbirth. Those conditions were not unavoidable; we could regard them as instances of injustice.

In 2008, one year after I was appointed, I convened a summit on the Millennium Development Goals. I really wanted to give some political input to catalyze an understanding of the importance of meeting the MDGs. From that time onward, I convened MDG summit meetings, and summits on climate change, one after another, until the last year of my term as Secretary General. With all that effort we were able to make significant progress towards most of the Millennium Development Goals, but many things were left unfinished.

The eight goals were welcomed,but not much political supportwas given. The goals ended up forgotten for the most part, left to government ministries and such to achieve. Not even the business community got involved, let alone civil society. I thought that we had to make sure that by 2015, the target year, we did as much as we could to achieve the goals.

Through accelerated action by the United Nations and many governments, we were able to achieve goal number 1 five years before the target. In 2010, the World Bank announced proudly that goal number 1, the halving of the number of people living in abject poverty, had been achieved. In reality, though, that achievement was largely the result of efforts by China. The Chinese government had been working very hard to eliminate poverty, and by 2010 there were 450 million fewer Chinese people in poverty. As a result, the world statistics improved quickly: five years before the target date, the World Bank could announce that the goal had been reached. But there were still more than 800 million people starving. There were still 62 million children who were not able to go to school.

◆ Building on the MDGs

At the 2010 summit meeting, the member states mandated me to come up with a set of proposals. We reached out to the member states. Then, at the very important Rio+20 summit meeting held in 2012 in Rio de Janeiro on the 20th anniversary of the Rio Summit, we decided to discuss arrangements forthe successor to the MDGs.

In 2012, three years before 2015, the MDG target year, we were already working on the Sustainable Development Goals. We did not know then what they would be called, but we knew that we had to continue the MDG process. We reached out through our website, asking the opinions of people around the world. We contacted nine million people: young people, women, people with physical disabilities, politicians, business people, academics. We reached out and heard their aspirations, the ways in which they really wanted to make this world better. We were surprised to receive so many answers from the UN member states and from people around the world. Most were not government officials, they were ordinary citizens. There were thousands of pages of good ideas. We worked hard to process them all.

We did not know that we would end up with 17 goals, but we were sure that the ideas we received were representative.

Government officials also contributed greatly. We established a preparatory committee, led as before by both developing and developed countries. This was not just a few people sitting together and writing down some ideas. The preparations were intense; the SDGs were the result of extensive, hard-fought negotiations among the member states. In 2012 the UN member states adopted a 35-page long set of recommendations for sustainable development goals, condensed from 6,000 long documents.

Then, in 2013, when I convened another summit meeting on the Millennium Development Goals and the SDGs, the member states mandated me to come up with some proposals. Because 2015 was the last target year of the Millennium Development Goals, we set that year as the target for the creation of a suc- cessor to the MDGs, a plan that would apply to both developing and developed countries.

◆ Underlying philosophy

That’s a sketch of how the SDGs emerged. The planning involved some philosophical elements, for example something drawn from President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s famous Four Freedoms speech. In

1941 he identified four essential freedoms: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. No person on earth should be denied these four freedoms.

Another philosophical element was the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. That document declares that we each have the right to a standard of living that ensures our health and well-being and that of our family.

A most important philosophical element of the SDG work is the United Nations Charter, adapted in 1945, which promotes social progress and a better standard of life in an atmosphere of greater freedom.

On September 25-27, 2015, we convened the United Nations Sustainable Development Summit 2015. Almost all the heads of state and government leaders came. Japanese Prime Minister Abe was in attendance. Even Pope Francis came to the United Nations for the meeting, the first pope ever to do so.

At the end of a concert or other performance, there is usually a standing ovation with sustained applause. However, I have never seen such extended applause as we say in the standing ovation by all the heads of state and government. That was a most moving moment. There were no ideological disputes, no political exchanges, just that united feeling. I can never forget that moment. I was hoping that the United Nations General Assembly and the Security Council could always be like that, without any conflict or division.

◆ A truly comprehensive set of issues

As I mentioned earlier, with the MDGs we were able to halve the number of people living in poverty. We were able to reduce the number of under-five child mortalities by 45%. We were able to provide at least 2.6 billion people with access to water and electricity — of course it’s true that still we have 886 million people in the world who do not have access to sufficient food, 1.4 billion without electricity, and more than 1.2 billion without sanitation or safe water. These are just a few examples of the importance of working to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

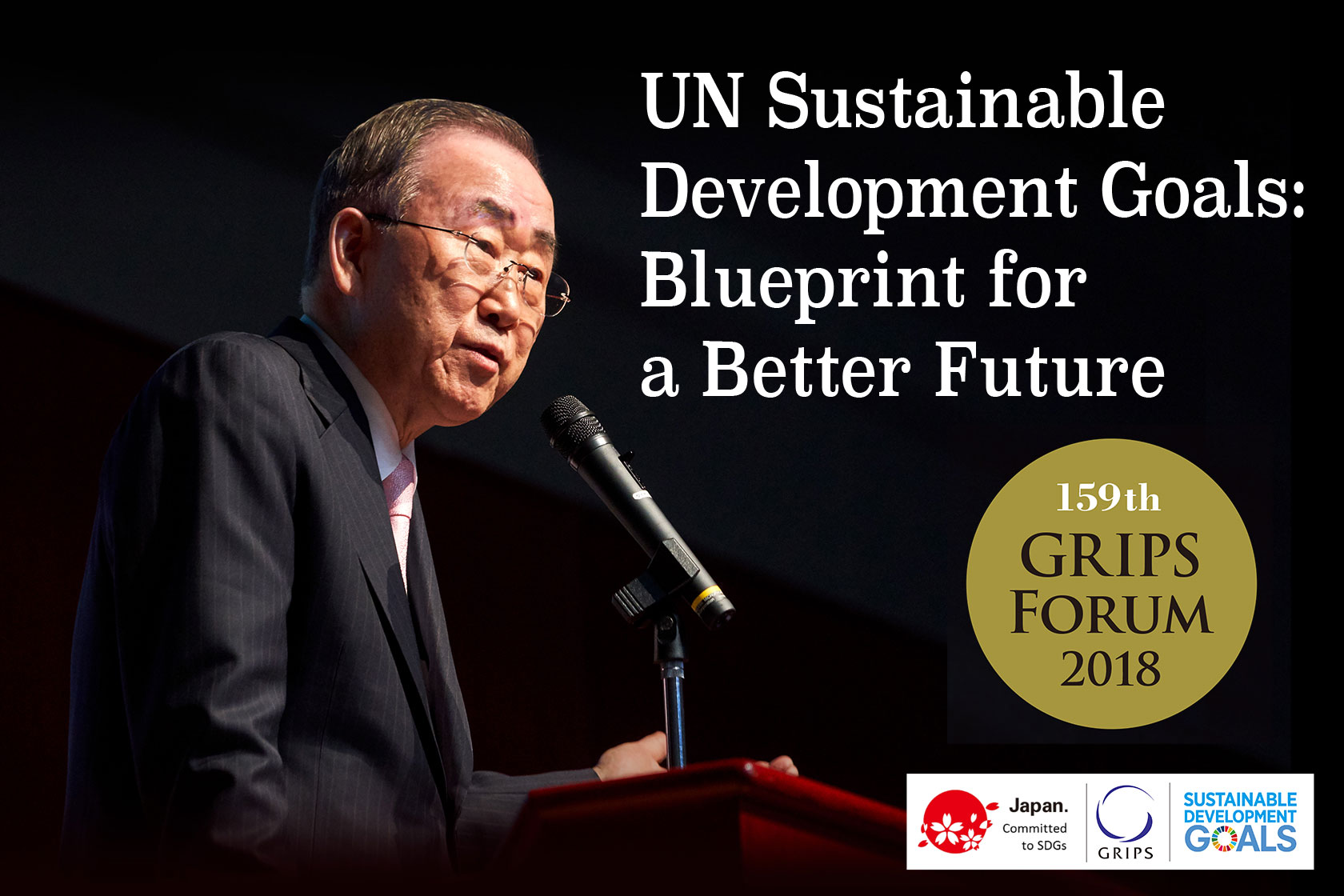

The SDGs aim to address the unfinished business of the MDGs. There is a great expansion of scope in the 17 goals, which range from completely eliminating abject poverty to forging global partnerships.

This year, I met China’s President Xi Jinping. He said that by 2020 (which is 10 years ahead of the SDG target) not a single Chinese would be living in abject poverty. He was quite confident; he said, “I can do it.” I hope China can achieve that goal. Our aim is that by 2030, there should be 100% achievement of SDG 1. It’s a very ambitious objective.

Some of the SDGs, especially SDG 13, are related to environmental improvement, particularly to climate change issues. SDG 14 is aimed at preserving the environment in terms of measures such as ocean diversity and marine diversity. There are at least five SDGs related to the environment, it’s that important. There are four goals related to economic growth. And of course, peace is an essential goal.

You could say that the 17 SDGs cover every aspect of our life.

There was serious discussion about goal 16, which is about peace, justice, and strong institutions. This is a rather political set of issues. What do we mean when we talk about strong institutions, about justice, about peace? Development, peace, and security are tightly interconnected: without strong institutions, you cannot achieve the other goals.

◆ Ensuring accountability

In this work, we have to ensure accountability in the use of funds. If there is no justice system in place, if there is no accountability, then all the money and resources allocated for the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals might end up being used for different purposes. We need detailed goals to ensure transparency. That is why each of these 17 broad goals is defined in terms of several targets, which in turn are each measurable by a number of indicators. In that way we can review the degree of implementation economically, scientifically and statistically. That is why I appointed a number of commissions, including The Scientific Advisory Board of the UN Secretary-General, a high-level The UN Statistical Commission. We needed their evaluations to oversee the work towards these goals and targets and make the work as comprehensive as we can imagine. You can see why it took three full years to negotiate the SDGs.

◆ Goals to be proud of

I think the SDGs are by far the mostscientific, most comprehensive, mostambitious set of goals that the UnitedNations has ever presented to the world.In that regard, I am very happy andproud to have been a part of this process.Now, more than three years after theadoption of the goals, what is the statusof the work towards them? At this moment, 102 countries have reported theirprogress to the United Nations. In 2016 the United Nations added a review mechanism, the High-Level Political Forum, a collaboration of heads of state and government.

The United Nations has placed these goals in the hands of each and every government. I asked the leaders to establish dedicated task forces to make sure that the Sustainable Development Goals and the Climate Change Agreement were implemented under the direct supervision and guidance of national leaders, prime ministers and presidents. Prime Minister Abe immediately established an SDG implementation headquarters under his direct leadership. Now the presidents and prime ministers of many other countries are doing the same.

◆ Leave no one behind

There are many people who are living in very dire circumstances, including people with physical disabilities, girls and women, people of different sexual orientation, and groups who are excluded by discrimination from normal life in our societies. We have to make absolutely sure that all these people are included in our work to make this a fair world.

Emergent urgent goal: Climate change response

The 17 SDGs are political arrangements that should be implemented for the betterment of humanity. They are open to agreement or disagreement. On the other hand, the Paris Climate Change Agreement is a treaty, a binding legal agreement that must be implemented. Unlike the SDGs, it has legal status.I am deeply concerned that some countries, par- ticularly the United States, the world’s largest and most resource-rich country, are withdrawing from the Paris Agreement. The US is the second largest greenhouse gas emitter, responsible for about 14% of global greenhouse gas emissions. China produces 24%, so together, China and the United States are responsible for almost 40% of global emissions. The United States is now withdrawing from the agree- ment; this is causing a lot of political damage, with a lot of political, if not legal, consequences. Nevertheless, I am encouraged to note that people around the world, even people in the United States, are moving ahead on climate.

The IPCC, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, composed of more than 2,000 scientists from around the world, has determined that the climate change we are experiencing is the result of human behavior, particularly during the 200 years since the industrial revolution. It’s only natural that we have to alter our patterns of consumption and production. The business communities really have to adjust their operations in a climate friendly way. Each and every citizen has to change their behavior.

We have to use water, energy and resources very sparingly. We have an urgent mandate to live harmoniously with nature.One bit of good news is that the World Bank has announced that they will provide $200 billion for climate work in the next five years. Well, $200 billion is a huge sum, but it is not enough. The developing countries have contributed the least to the current climate phenomena, but they are the ones who have been hit most seriously by climate change because they do not have the capacity to mitigate its impact or adapt to it. We have to mobilize much, much more money to assist the developing countries in climate work. The developed world has already promised $100 billion a year to support developing countries in their adaptation and mitigation efforts, but I have been urging the countries of the OECD to support the developing countries on an even larger scale.

◆ Startling evidence of climate impact

I went to the Aral Sea recently, for the second time. It was really shocking. The Aral Sea used to be the world’s fourth largest lake. It has shrunk to just 10% of what it was. 90% of that vast body of water has completely dried up. Now it’s a salt bed with a lot of ships marooned on the sand, far from the nearest water. That was a man-made disaster. The Soviet Union diverted Aral water to cotton fields to the point where the Aral Sea almost completely dried up. The salt from the soil, along with industrial chemicals, is damaging the ecosystem over a vast area. Similarly, Lake Chad has shrunk to 1/16th of its original size in just 30 or 40 years. Now we are working very hard to reverse such ecological impacts.

We have to make sure that the environment of our world is sustainable. First of all, though, we have to be able to live on this planet. I am asking world leaders, political leaders, to take both political and moral responsibility in this regard, but in fact I think we all share in that moral responsibility. Whatever we do should be good for our succeeding generations, good for our world. We have only one planet Earth. Within the range of our technology and science, we have never found another planet where human beings or animals or plants could live. This Earth is the only place we have. We have to make sure that the Climate Change Agreement is implemented.

Message from Mr. Ban

I think we each have a moral voice. Young people, students in particular: you have the right to vote, so challenge your leaders and make sure that your society is livable and environmentally and economically sustainable. Before you assume leadership in the near future, I think you need to begin to work as global citizens. For bureaucratic reasons, you have to carry the passport issued by your country, but you are no longer only simply citizens of Japan or Korea or Uzbekistan: you are global citizens. That is my request to you: act as global citizens. You are our only hope. We must make sure that the peo- ple of the future will live in a globalized society.

◆ Q&A Questions from participants

—You mentioned some essential ingredients for a sustainable society. I suggest that another key ingredient is sharing, for example, sharing wealth, sharing capability, sharing happiness, and particularly spiritual happiness. I think that is the most fundamental human obligation. What do you think are the keys to a sustainability society?

Mr. Ban That is a political question. I fully agree with your point about sharing. We have to share our resources and share our common goods, but really, in real life, these resources are not evenly distributed. That is why we have been working to make very sure that all the wealth and resources and benefits allotted for work on the Sustainable Development Goals are equitably shared.

We should all be able to live with human dignity. However much money or wealth you may have, if all humans are not treated with dignity, then what is the difference between us humans and other animals? That is why human rights is a very important con- sideration. As I said earlier when I talked about the philosophical or political background of this work, freedom from want and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights are very important philosophical considerations, and the Sustainable Development Goals are based on them.

—You mentioned that some of the big powers are withdrawing from the climate change negotiations. A similar situation is arising related to the Global Compact for Migration, a draft agreement agreed made in July 2018, with 190 nations in agreement. Recently some countries who signed onto that draft agreement have indicated that they may not attend the signing of the Global Compact for Migration. This is an alarming sign for multilateral diplomacy. States are placing more importance on their nation- al interests than on the greater good. What do you think is going to happen to multilateralism? Will regionalism will be the next trend in diplomacy?

Mr. Ban First, let me say that as former Secretary General of the United Nations, I am deeply concerned to see multilateralism under threat. Nationalism, extremism and individualism are on the rise. There are political leaders who are erecting walls between and among people. I have been strongly urging the leaders not to erect walls, but rather to ensure that there will be free movement of people and increasing interaction. It is human nature to move: for thousands of years, people have been moving from one place to another to better their lives.

I am also very concerned about emergent protec- tionism and trade wars. This is reminiscent of what happened in the 1920s and 1930s when the United States was strongly isolationist, laying on tariffs like the notorious Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, domestic legislation which created serious global problems. Some 90 years ago, the international community was suffering from a global financial crisis. Now there is a fear that we might suffer another.

Until recently the nations of the world were united in facing this threat. At the first three G20 summit meetings, there was real solidarity. Now at the fourth G20 summit, people were speaking differently. There was a lot of talk about trade protection and nationalism, about putting your country first, for example the America First policy. But no country can live in isolation. We are living in a time of transformative developments in science and technology, and we are in fact living in a very small world. In that context I must speak out strongly against iso- lationism.

At this time twelve countries have backed out of the Global Compact for Migration, a most unfortunate development. It started with the United States, then Poland, Hungary, then Austria.

As you said, this is not a binding treaty. However, we have to show compassionate leadership in sup- porting the many people who really desperately need our help. How we can ignore their plight? When they reach out, we should take their hands, rather than turning away. Turning away is not politically right. It is not morally right.

—As you mentioned, China, and for that matter, the developing countries, have been working hard to reduce poverty in this world. But at the same time, some developing countries are among the biggest emitters of greenhouse gases. How can we reconcile this dilemma?

Mr. Ban We appreciate that China is making a great effort on poverty, but at the same time China is the biggest emitter. What is important is that they realize that they have to do much more about emissions. This Climate Change Agreement was difficult because countries like China and India, big emitters, were very reluctant to get on board with this nego- tiation because they were afraid they might have to change their social and economic systems and infrastructure a lot. Eventually they realized that it would be better to join now, rather than pay more and make more sacrifices later.

For example, there has been serious debate about whether the target temperature increase should be 1.5 degrees or 2 degrees,and where it should apply.Small developing islandcountries are sinkingbecause sea level is rising. They are urging strong containment of global temperature rise. However, that will require huge changes in infrastructure. The Paris Climate Change accord says 2 degrees, but very recently, the IPCC recommended that global temperature rise should be kept below 1.5 degrees. However, this is not a treaty, it’s just an urgent recommendation by scientists.

I think the OECD countries should take political and moral responsibility, but they are very reluctant to come up with the money. That is why the World Bank has announced that it will pay $200 billion: it’s a political message to spur countries to action, to catalyze the world’s people, particularly those in industrialized nations.

The Alliance of CEO Climate Leaders, fifty leaders of big companies with a total annual production of 1.3 trillion dollars, recently announced their actions on climate change in terms of adjusting their business operations and providing financial support. I hope that will gain momentum. We can’t expect governments to pay everything; they have limited resources.

—You said the United States is responsible for 14% of total greenhouse emissions in the world today. What actions are actually being taken by the United Nations and its member states to urge the United States to stick to its obligation to reduce greenhouse gas emission?

Mr. Ban I think each and every one of us, not just political leaders, should speak out on this topic. Normally political leaders do not speak out against any very powerful country. I have spoken repeatedly against President Trump’s decision, and I’ll say it again here. His decision is politically shortsighted, economically irresponsible, and scientifically dead wrong. He and the US will be standing on the wrong side of history. This is my message, a warning. It is politically and morally irresponsible if the rich and powerful nations do not help those countries who contributed so little to climate damage but are the most seriously affected.

Civil society, students, you can speak out, you can write some letters, you can write in the media. Use your voice. That is your responsibility. The political leaders in particular are not speaking out. When it’s a major sovereign power like the United States holding back, that is clearly not right.