(See handout no.13; readings McKinnon-Pill, Kaminsky et al)

This lecture takes a look at three studies related to currency crisis. They are (i) amplification of banks' moral hazard problem under financial integration (McKinnon and Pill); (ii) review of the first and second generation models of currency crisis; and (iii) a currency crisis early warning system (Kaminsky, Lizondo and Reinhart).

For this model, see McKinnon and Pill (reading B2).

Professor Ronald McKinnon of Stanford University and his former student Huw Pill wrote a paper on the overborrowing syndrome of developing countries. Their argument is roughly as follows: when the domestic banking system is plagued by the moral hazard problem, opening up of the financial sector to the rest of the world will induce huge overborrowing and bad debt. In other words, financial integration magnifies a domestic problem.

McKinnon previously wrote a book, The Order of Economic Liberalization (1993), where he argued that liberalization of goods and financial markets must proceed in the right speed and sequence to avoid unnecessary shocks and difficulties. The McKinnon-Pill paper is along the same line of research.

Consider a simple 2-period investment model. This formulation is one variation of the current-account model based on inter-temporal optimization. McKinnon and Pill developed the argument graphically.

The economy has two investment projects: small and large. The small project requires only a small initial capital which can be generated by family saving or loans from relatives (i.e., only informal finance is necessary). For example, running a family shop or raising a few cows belong to this category. On the other hand, the large project requires a huge initial investment which must be borrowed from a bank. This is typically an investment in a modern factory with expensive machines.

McKinnon and Pill explains the economy's equilibria step by step, from the most repressed to the most liberalized, to show how and where the overborrowing is generated.

Financially Repressed Economy (FRE)

In the financially repressed economy, banks do not function because the government taxes them too much through high inflation and regulation (high reserve ratios). There is a big gap between lending and deposit interest rates. Or maybe the banking sector is simply too underdeveloped, or people fear deposit confiscation. As a result, no one really uses the banks. Banks function as the government's fiscal agents, and only those enterprises (typically SOEs) required to have deposits with banks use them.

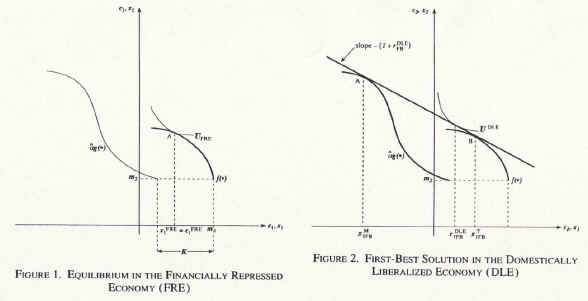

We assume there is no future uncertainty at this point. In addition, international capital transactions are severely controlled. Since there is only informal finance, small projects are undertaken but not large ones. Large projects may yield higher returns, but such potential is not realized (Fig.1)

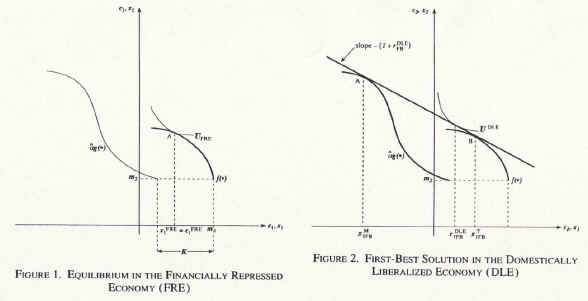

In the graphs below, today's goods are measured horizontally while tomorrow's goods are measured vertically. The curved line on the right represents the small project while the elongated reverse-S shape on the left represents the large project. The twist in the long project curve means it exhibits increasing returns at first, then decreasing returns. The amount of investment is measured horizontally from right to left.

Domestically Liberalized Economy (DLE)

Suppose the domestic banks are liberalized. This means that the government no longer levies high taxes on the banking sector, so the gap between lending and borrowing interest rates narrows (or disappears). In addition, let us assume that banks are well monitored by the monetary authority so they do not lend excessively or recklessly. Now people begin to use banks for deposits and investment.

We still assume that future is certain and there is no free international capital mobility.

Under this situation, normally (unless we are stuck at a corner solution due to the shape of preferences), both small and large projects are undertaken. Large projects are financed by bank lending. Small projects may be financed informally or through banks. The domestic interest rate is determined so that the returns to both projects are equalized (Fig.2 above)

DLE with uncertainty

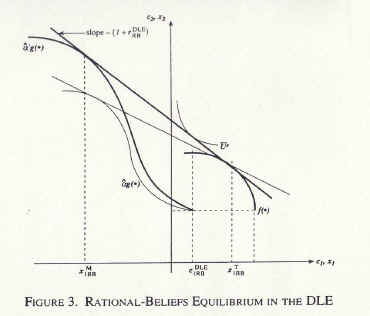

Let us now introduce uncertainty. We assume that the return to the large project is stochastic (different outcomes are possible with fixed probabilities), so the project may yield a good result or a bad result. If the banks are risk-neutral (they only care about the average results in the long run), their lending behavior and the interest rate will be determined by the average outcome. If so, there is no general overlending even though the large projects sometimes succeed and other times fail.

But suppose there are informational problems. Moral hazard is a situation where someone's behavior becomes unnecessarily risky while adverse selection is a problem caused by inability to distinguish risky borrowers (or insured people) from safe ones. More precisely,

Moral hazard is a situation where a person takes excessive risks ex ante due to the existence of insurance or guarantee against a bad situation ex post. If you have a fire insurance, you tend to be less careful with fire. If you have a car insurance, you may drive less carefully. And in the case of banking, if the government guarantees to pay the depositors in full in case of crisis, banks will be less careful in selecting projects and borrowers. They want to lend to very risky but seemingly high return projects. If the project succeeds, banks receive high returns. If the project fails, banks can ask the government to bail them out. If you are well connected with the government, your bank will survive even in a crisis ("too big to fail," "we must avoid systemic financial crisis," etc).

Adverse selection is related to a situation where you are unable to tell the risky group from the safe group. You are therefore forced to set the same participating condition (insurance premium, interest rate, etc) for the two groups. But under this circumstance, only risky people will be attracted. For example, if you cannot tell sick people from healthy, you must offer a life insurance based on average health statistics. But such an insurance is attractive only for the sick, so only they will participate. In the case of banking, if the banker is unable to distinguish good projects (or borrowers) from bad, and set the interest rate accordingly, he will attract only bad projects (or borrowers).

In the McKinnon-Pill model, moral hazard is the key problem. Since the government (explicitly or implicitly) guarantees deposits, if the projects succeed, banks get high returns; and if they fail, the government will bail them out (instead of jailing--or executing--the manager and confiscating all his assets). Banks only think of the good outcome and lend excessively to high-risk, high-return projects--namely, they overlend. The domestic interest rate will be higher because of this. The economy will exhibit over-investment in the first period compared with the case without moral hazard. But this overspending is relatively small when the economy is not integrated with the global financial market (because there is only a limited amount of capital available domestically).

On the left side of Fig. 3, the thinner line shows the average outcome of the big project while the bold line shows the good outcome. People choose the consumption point based on the good outcome rather than the average.

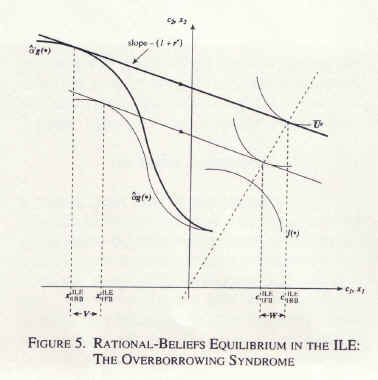

Internationally Liberalized Economy (ILE)

But now, we open up the economy financially, without solving the moral hazard problem. The interest rate is no longer determined domestically, but internationally (we assume that the world interest rate is lower than the domestic rate which prevailed under DLE).

In this situation, everyone who has the opportunity will borrow from abroad (through banks) and invest in the large project. The small project is now dominated by the large project in terms of rate of return.

Moreover, because of the moral hazard problem, banks' lending behavior is based on the best outcome, not average. If a good situation materializes, fine. But if the outcome is average or bad, people will have to compress consumption in the second period below expectation, or even default on the loans. In this way, external financial liberalization amplifies the banks' moral hazard problem.

See reading B1 for more description. See also the appendix of Reading A.

First generation models

In the early 1980s, the first generation models of currency crisis were constructed. The idea is a very simple one. The model assumes that there is something wrong with economic fundamentals: a policy inconsistent with a fixed exchange rate is adopted (for example, excessive monetary growth). If that policy persists, the exchange rate will ultimately have to collapse. The question is "exactly when will it collapse?"

Consider an economy represented by the following four equations (in logs):

m - p = - a i (money market; a is positive)

m = d + r (money supply is a sum of domestic credit d and reserves r)

p = p* + s (purchasing power parity, where s is the exchange rate)

i = i* + (change in s) (uncovered interest parity)

Let us assume that domestic credit (d) is increased at a certain rate (continuously and regardless of whatever happens to the exchange rate) and the exchange rate (s) is initially fixed.

Before the speculative attack occurs, s is fixed, and so are p and i. If p and i are fixed, m is also fixed (first equation). Since the nominal money stock is fixed, but d is always increasing, the country is losing international reserves (r) at the same speed as the issuance of d.

When the speculative attack occurs, international reserves jump down to zero (r = 0), and the exchange rate begins to float. Domestic credit (d) continues to grow as before, and the exchange rate begins to depreciate at the same rate as the increase in d.

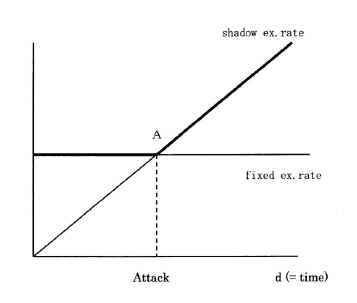

The question: when does the speculative attack occur? To think about this, consider the shadow exchange rate which is a hypothetical exchange rate that would be realized immediately after the attack. If this level is below the initial fixed rate, speculation will appreciate the home currency and depreciate the dollar, so there is no incentive to buy the dollar. If the shadow exchange rate is above the fixed rate, the attack will depreciate the home currency and appreciate the dollar, so everyone wants to attack. But because of competition among speculators, the actual attack will come exactly where the fixed rate and the shadow exchange rate intersect. The exchange rate smoothly moves from fixed to floating without a jump. Before this point, attack does not pay. After this point, attack is too late (since everyone else has already attacked).

In a sense, this model is trivial as far as the cause of crisis is concerned. If the central bank continues to create money too fast, there is no wonder that the attack comes eventually. The only question is timing--it is determined by competition and expectation among currency traders. The policy lesson is clear: do not have big budget deficits or high money growth. Sound macro policy will protect you from currency attacks.

Second generation models

The second generation models of currency crisis is a bit more complex to explain. Attack may come even if economic fundamentals are good. In other words, good policy does not necessarily protect you from attacks. These models capture the inherent instability of the private currency market.

Technically, the model is based on some kind of nonlinearity in the policy reaction function. If the policy is linear (roughly speaking, the policy is the same before and after the attack), there is usually only one solution to the model. But if it is not linear (the policy changes before and after the attack), there is a possibility of multiple equilibria--an equilibrium with attack and an equilibrium without attack are both possible.

For example, this can occur when the government is pursuing two goals. It wants to have a fixed exchange rate on the other hand, but it also wants to keep unemployment down (or alternatively, keep interest rates low, protect banks' balance sheets, contain external debt burden, etc) on the other. Tight money supports the fixed exchange rate but worsens the other situation. While the government is able to maintain exchange rate stability by tight macro policy, it may choose to do so. But when a big attack comes, maintaining the exchange rate becomes too costly, and the government will switch to the other regime of floating the currency and achieving the domestic goal. In other words, the policy of fixing the exchange rate under some domestic strain and the policy of giving up currency stability and achieving domestic goals are both possible. Which one will be realized depends on whether the market attacks or not. The first solution is chosen if the market does not attack, but the second solution is chosen if the attack comes. It is the market, not the government, who decides.

The above explanation is just one example. There are many other ways to model policy nonlinearity and have similar indeterminate results. Another point: the second generation models can show the possibility of multiple equilibria but cannot tell us which outcome (attack solution or non-attack solution) is more likely to emerge empirically. In other words, the theory takes the market psychology as externally given, instead of explaining it.

The following phenomena, which are mutually related, are associated with the second generation models:

Self-fulfilling attack: if the market decides to attack, a currency crisis will occur. If the market chooses not to attack, a crisis will not happen. Any news or rumor (whether true or false) that affects the market sentiment may start a crisis. Whether the country's policy is good or bad is, in this sense, irrelevant.Herding: currency traders and international investors may behave like a herd of buffalos. If the leader goes in one direction, all others will follow without thinking. As a result, all of them may go over a cliff. Their behavior is not rational or based on solid facts. Investors invest in fashionable assets, but they do not really know very much about these assets.

Information cascade: if one person (say, a market analyst) says that country A has a trouble, some people begin to believe it. Because some believe it, more and more people come to believe it, until everyone is pessimistic about this country--but in reality, the first analyst may be wrong, and there may be no problem with country A ! Once started, information spreads like avalanche and no one can stop it.

|

|

| A currency continues to fall and traders panic... typical scenes from currency crisis | |

The first and second generation models have very different policy implications. In the first generation models, the crisis is caused by problems in fundamentals. Bad policy invites attacks, so correct the policy. But the second generation model points to inherent instability in private sector behavior. If financial markets are inherently unstable and damaging, a free economy may not be such a good thing. The government should regulate markets rather than let them work freely.

For this, see Reading B1

Can currency crises be predicted?--asked some IMF economists (Kaminsky, Lizondo and Reinhart). They posed this question slightly before the Asian crisis erupted in 1997. The following is the summary of their arguments.

Definition of a currency crisis

First, they define "currency crisis" as a large exchange rate depreciation or a large international reserve loss, or both. Using the monthly data for each country, they normalize (i.e., divide by standard deviation so each variable has unit variance) the changes in the exchange rate and international reserves. Then the two time series are added to create a new variable. A "currency crisis" is defined as the period when this combined variable is over three standard errors above the mean in the "bad" direction. [It may also be possible to use high short-term interest rates as an additional indicator--because depreciation, intervention (losing reserves) and high interest rates are the three common responses to currency attacks.]

As noted in the previous lecture, currency crises are not uncommon. There have been many instances of them in history.

Literature review

According to the authors, there are three types of currency crisis studies.

The first is descriptive. Using no statistical analysis beyond simple tables and graphs, most studies describe the occurrence of currency crisis chronologically and identify "stylized facts" (=common patterns).

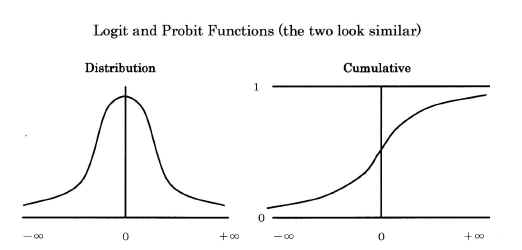

The second is the logit/probit model. These models estimate a probability relationship with a discrete dependent variable (one or zero, or a crisis happens or does not happen). Both logit and probit functions are symmetric, smooth, increasing and takes the value between zero and one. The data of zero (no crisis) or one (crisis) is regressed on this nonlinear function with many explanatory variables (overvaluation, monetary growth, current account, international reserves, etc). This estimation can tell us which variable has a predictive power. It can also show the probability of a future crisis.

The probit function is the same as the normal distribution. The logit function has the basic form: 1/[1+e^(-x)].

The third is the signals approach. Instead of summarizing the probability of crisis in one number between zero and one, this method looks at different explanatory variables separately. A variable is considered to be issuing a warning signal if it goes beyond a certain "threshold" level in the bad direction. This threshold is statistically determined. Some variables are reliable signals while others are not. Variables are ranked according to certain criteria. If many reliable signals issue warnings simultaneously, we must be careful.

Kaminsky, Lizondo and Reinhard adopt the third method.

Selecting signals

The authors look at monthly data of a large number of candidate explanatory variables for each country. These variables are converted to the percentage change per year. The forecast scope is two-years.

When a warning signal is issued, there are two possibilities: (i) a crisis will occur (correct), or (ii) a crisis will not occur (false). When a warning signal is not issued, there are also two possibilities: (i) a crisis will occur (false), or (ii) a crisis will not occur (correct). The ranking criterion is constructed to minimize the two types of errors (it is like choosing the best signal-to-noise ratio). Table 1 (in Reading B1) presents the final result. The candidate variables are shown in the order of descending reliability as warning signals. (In Table 5 of handout no.13, which is based on the Working Paper version of the same paper, the results are slightly different.)

Five Most Reliable Early Warning Signals of Currency Crisis (Working Paper Version)

| Signal | Warning is issued when: | |

| 1 | Real exchange rate | The home currency is overvalued. |

| 2 | Exports | The value of exports fall. |

| 3 | Stock prices | The stock market index declines. |

| 4 | M2/international reserves | International reserves are too small relative to money. |

| 5 | Output | There is a recession. |

The real exchange rate is the best predictor of future currency crisis. When the home currency is overvalued, currency crisis is most likely to occur. The second best signal is export performance, the third best is stock price movements, and so on. The first 11 or 12 variables have positive values as warning signals. The remaining variables are of no value, since their performance is worse than simply casting dice.

In the aftermath of the Asian crisis, I constructed a similar table of warning signals for Vietnam. But this exercise had to be greatly compromised or revised due to the lack of data. First, only annual data were available on a consistent basis, not monthly, so standard errors could not be meaningfully calculated. Second, the stock price was not available since Vietnam did not have a stock exchange at that time (now it does). Third, I added three qualitative data which seemed important for Vietnam: FDI inflow, currency crisis in the region, and market perception of currency overvaluation. This is a crude attempt at the signals approach when data are very limited.

In light of the experience at the time of the Asian crisis, it is now customary to add the nation's short-term debt as one of the key explanatory variables in crisis prediction.

Some questions

Does this kind of prediction really work? Certainly, it is a good thing for the policy authority to constantly watch for irregularities in key macroeconomic variables and take corrective action. But the predictive power of the signals approach as described above is in question. Here are some reasons.

--There are considerable cross-country differences in the causes of currency crisis. East Asia had banking problems, while Russia and Latin America had large fiscal deficits. The signals approach tries to capture the average tendency, but what is the meaning of "average" when different types of crisis exist?--Statistically, out-of-sample predictability is known to be much lower than in-sample fit. In plain English, it is more difficult to predict the future than to explain the past patterns.

--More fundamentally, as we saw above, the second generations models of currency crisis point to the possibility of attacks even when macroeconomic fundamentals are sound. Currency crisis may occur due to unstable global market sentiments. If so, trying to predict future crisis from domestic macroeconomic variables alone is futile.

Since 1999, IMF economists have been monitoring the performance of several early warning models (Berg, Borensztein and Pattillo, 2004). Out of sample, they find that the Kaminsky-Lizondo-Reinhart model above performs reasonably, while the IMF's other in-house model (based on probit regression) performs less well. Private sector forecasting models perform poorly. However, it may be too soon to evaluate the performance of these models given the very short period available for out-of-sample forecast.

<References>

Andrew, Berg, Eduardo R. Borensztein, and Catherine A. Pattillo, "Assessing Early Warning Systems: How Have They Worked in Practice?" IMF Working Paper WP/ 04/52, March 2004.

Flood, Robert, and Nancy Marion, "Perspectives on the Recent Currency Crisis Literature," NBER Working Paper no. 6360, January 1998.

Kaminsky, Garciela, Saul Lizondo, and Carmen M. Reinhart, "Leading Indicators of Currency Crisis," IMF Staff Papers 45:1, March 1998, pp.1-48. (IMF Working Paper version: 1997).

Krugman, Paul, "A Model of Balance-of-Payments Crises," Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 11, 1979, pp.311-325.

McKinnon, Ronald I., The Order of Economic Liberalization: Financial Control in the Transition to a Market Economy, Johns Hopskins University Press, 1991. Revised 1993.

McKinnon, Ronald I., and Huw Pill, "Credible Economic Liberalizations and Overborrowing, " American Economic Review 87:2, May 1997, pp.189-193.

World Bank, Private Capital Flows to Developing Countries: The Road to Financial Integration, Oxford University Press, 1997.