|

|

|

|

Amata Industrial Park (by Thailand) in Southern Vietnam (left); and Canon inkjet printer factory in Northern Vietnam. |

|

(See handout no.6)

This topic properly belongs to the real side (trade and investment) rather than the financial side of international economics. However, we will discuss it anyway since (i) it is an important topic; and (ii) my current research in Vietnam (and East Asia) deals with this issue. This lecture is mainly based on the experience of East Asia, with possible applicability in other developing regions.

|

|

|

|

Amata Industrial Park (by Thailand) in Southern Vietnam (left); and Canon inkjet printer factory in Northern Vietnam. |

|

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is also called "direct foreign investment (DFI)", "direct investment", or "foreign investment." It is an activity where foreigners come to your country to set up and/or run a factory, hotel, farms, or other business enterprises. More precisely, here are some definitions of FDI (my italic):

Definition #1: "Direct investment refers to investment that is made to acquire a lasting interest in an enterprise operating in an economy other than that of the investor, the investor's purpose being to have an effective voice in the management of the enterprise." [IMF Balance of Payments Manual, 4th ed, 1977, p.136]

Definition #2: "The balance-of-payments accounts define direct investment as that part of capital flows that represents a direct financial flow from a parent company to an overseas firm that it controls." [E.M. Graham and P.R. Krugman, "The Surge in FDI in the 1980s"]

Definition #3: "Direct investment is intended to comprise investments involving a certain degree of control (by the investor) over the use of the funds invested, whereas portfolio investment lacks such control." [Rivera-Batiz & Rivera-Batiz, p.220)

It is clear from the above that FDI intends to "control" or, more mildly, "participate in" the management of a business enterprise. Thus, my definition is:

Definition #4: FDI is an international financial flow with the intention of controlling or participating in the management of an enterprise in a foreign country. [K Ohno]

FDI is contrasted to "portfolio investment" where there is no intention or interest to control an enterprise. The purpose of portfolio investment is to get a good financial return as in the case of investing in stocks, bonds, gold, art objects, etc.

Operationally, there are three types of FDI:

(1) Equity acquisition--buying shares of an existing or a newly created enterprise

(2) Profit re-investment--FDI firms re-investing their profits for further expansion

(3) Loans from a parent company

In additional terminology, if foreigners come to build an entirely new factory (rather than buying an existing one), it is called greenfield-type FDI.

In addition to 100% foreign-owned firms, there are also "joint venture" (JV) firms where foreigners and domestic partners set up a company together. The ratio of ownership (shareholding) varies from company to company. In some countries there are restrictions on how much foreigners are permitted to own (say, up to 49%). Ownership restriction may be imposed on only certain "sensitive" sectors. In other countries, there is no such restriction and 100% foreign ownership is acceptable.

While the theoretical definition of FDI is clear, in reality there are serious measurement problems. For example,

(1) Whether a foreign investor has an intention to control or participate in the management is not directly observable. In the Japanese and US balance-of-payments statistics, investment is considered FDI if the foreign share is 10% or more; otherwise, it is classified as portfolio investment. Clearly, this rule is a bit arbitrary.(2) While a loan from the parent company is counted as FDI, a bank loan guaranteed by the parent company is not. Again, this is an arbitrary distinction since the two loans would have virtually the same economic effect.

(3) Whether the value of foreign investment is recorded at book value or at market value makes a difference. The latter changes due to inflation/deflation and capital gain/loss.

(4) Statistics for commitment (approval or promise to invest) is easier to collect, but actual implementation is more difficult to know.

Here are some general features of global FDI flows:

(1) FDI is less volatile than portfolio investment or bank loans. In the 1997-98 Asian crisis, capital inflows in the form of short-term bank loans suddenly reversed, but FDI did not leave the affected countries. In fact, FDI in the form of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) rose sharply after the crisis, as foreigners bought up local firms at low cost (i.e., at greatly depreciated exchange rates).(2) Generally speaking, FDI among developed countries is much greater than FDI from developed to developing countries. FDI among developing countries is very small. The only notable exception to this rule is China's huge absorption of FDI in recent years.

(3) Total FDI data includes mergers & acquisitions (M&A), setting up branch offices, service FDI, energy and mineral extraction, and so on. Greenfield-type manufacturing FDI, most desired by developing countries, is only a small part of FDI flows.

(4) Over time, popular destinations of FDI shift. From the viewpoint of Japan as a source country, the most popular FDI destination in the 1970s was NIEs (Hong Kong, Singapore, Korea, Taiwan). In the late 1980s it was ASEAN4 (especially Thailand and Malaysia). Since the 1990s to present, China has emerged as the most popular FDI destination in the entire developing world.

(5) As far as Japanese companies are concerned, the main motive for investing in East Asia is the pursuit of low cost and the building of regional production networks. However, the main motive for investing in EU and NAFTA (US-Canada-Mexico) is market access. This includes producing within a free trade area (FTA) or customs union so that tariff exemption and other benefits are enjoyed.

East Asia has emerged from the situation of wars, crises and stagnation in the early postwar period into the status of industrial competitiveness and higher standard of living within several decades. While there are different stages of development and growth performance among the East Asian countries, over time and as a region, their economic and social achievements have been outstanding. This is the only developing region that succeeded in catching up with the forerunners significantly and collectively (even with the setback suffered during the recent Asian crisis). This is in stark contrast with the other developing regions, especially Sub-Saharan Africa, where no such consistent progress is visible.

|

|

| Geese flying over the East Asian sky (photos by Saizou Uchida). The standard pattern is the reversed V shape, but there are variations. Some birds drop out while others join. The previous top bird (Japan) may be challenged by new comers (like China). | |

East Asian growth was realized by staggered (step-by-step) participation in the regional production network through trade and investment. The supply linkage was first formed between Japan and NIEs (Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore), then spread to include ASEAN4 (Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines, Indonesia). Later, China and Vietnam joined (this shifting pattern overlaps with the shift in Japan's FDI destination noted above). For them, development means jumping into this regional production network and becoming a meaningful player in it. The region provides an enabling environment for their industrialization. The World Bank's famous report, East Asian Miracle, in 1993, analyzed the policies of each country, one by one, to explain high regional growth. But the proper way to understand East Asian dynamism is to look at the region as an organic whole; its secret cannot be decomposed into individual parts.

Once captured by this regional dynamism, each country is under constant pressure to master technology, improve human capital and enhance competitiveness for survival. Multinational firms from Japan, Korea, EU and US play a key role as bringers of capital, technology, markets and management as well as agents of economic integration. Overseas Chinese capital is also a strong commercial power that contributes to the intra-regional linkage. On the demand side, it is noteworthy that East Asian growth heavily depends on the existence of huge external markets, especially American.

Through this process, East Asian countries raised income levels, and industries were passed from one country to another. This development formation is called the "flying geese pattern of development" (initially named by Prof. Kaname Akamatsu in the 1930s). The first bird (Japan) was followed by the next group of birds (NIEs), then another group (ASEAN4), then another (China, Vietnam), in a fairly orderly fashion. There is no other developing region that shows this kind of development pattern. We must say that Japan, the first bird, was relatively weak in the 1990s. On the other hand, China, the big latecomer bird, seems very strong. Some even say the flying geese pattern is already finished. But the clear structure still remains even though the order of birds may sometimes change.

|

Manufactured Export Ratio |

|

Late birds catching up to early birds and becoming exporters of manufactured products (as measured by the manufactured export ratio). |

|

|

Passing industries from the first bird to the second bird, and so on. FDI by multinational corporations (MNCs) is the agent of this industrial transfer. |

|

| Intra-regional trade (trade within East Asia) grows rapidly as parts are exchanged in international division of labor. |

Theoretically, there are three possible explanations why FDI occurs and production sites move from one country to another in this fashion.

The first is the factor proportion hypothesis. In conformity with the standard Heckscher-Ohlin trade model, this hypothesis says that the capital-labor ratio of a country determines what it produces. Low income countries with less capital and more labor (i.e., the K/L ratio is low) produces labor-intensive products while high income countries with more capital and less labor (i.e., the K/L ratio is high) produces capital-intensive products. According to this theory, as a labor abundant country accumulates capital through investment, its product mix will also shift.

The second is the technology ladder hypothesis. This says that production pattern is determined not so much by the simple capital-labor ratio, but whether a country can acquire necessary skills and technology to produce more complicated goods. For this, learning is very important. Learning must also be supported by appropriate education and training, ample supply of good managers and engineers, R&D, IT infrastructure, etc. According to this theory which emphasizes quality rather than quantity, countries with a lot of investment but no capacity improvement will waste resources and may not be able to establish new industries.

The third is the FDI dynamics hypothesis (or industrial cluster hypothesis). This view says that industrialization begins with an accumulation of a critical mass of FDI . Capital accumulation or technical mastery of the host country is not essential at the initial stage. Instead, what is crucial is whether or not the government can offer attractive FDI environment, especially free business environment and the low cost of doing business (which includes not only labor but also electricity, water, transportation, communication, housing, etc). At first, only cheap labor is utilized for simple assembly. But if assemblers successfully accumulate, parts suppliers gradually emerge (or come from abroad) and domestic procurement of parts and materials becomes possible. Once a virtuous circle between assemblers and parts suppliers is established, more and more investors (both assemblers and parts suppliers) will come. This is the situation now observed in the coastal areas of China (Guangdong and Shanghai areas). Capital accumulation and improvement of domestic capability will occur as a result of this process; they are not the cause of development.

Each of these theories has a different implication for policy makers. The first hypothesis says: invest. The second says: improve domestic capability. The third says: invite as much FDI as possible. At present, economists cannot say for sure which explanation is most convincing in the context of East Asian dynamism.

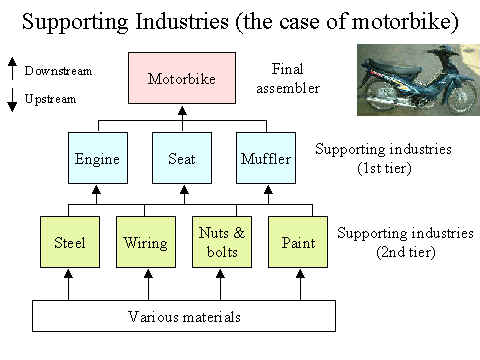

In the second and third hypotheses, the role of supporting industries is particularly important. Supporting industries (also called parts industries, ancillary industries, etc) are upstream industries that supply intermediate inputs to the final producer. Final assembly is usually easy but producing high-quality parts with high-quality materials is much more difficult. The value of the product is mostly determined by the quality of the upstream industries. Developing countries usually start with final assembly, and try to develop supporting industries later. But very few have succeeded so far. Thailand has accumulated automobile parts industries (Japan is the key investor) and Southern China has an accumulation of electronics parts industries (Taiwan is the major investor). Even in these cases, the host countries remain highly dependent on foreign technology, marketing and management. Key parts and materials often continue to be imported. The development of supporting industries is a big challenge for developing countries opting for FDI-driven growth.

Within East Asia, the patterns of industrialization in Northeast Asia and Southeast Asia are quite different.

Northeast Asia (Japan, Korea, and possibly Taiwan): In the early stages of industrialization, tariffs and policy loans were used heavily to protect and promote domestic enterprises. As they grow bigger and more competitive, protection and policy interventions were gradually removed. The state played the key role in directing resources. This is the classical "infant industry promotion" industrialization.Southeast Asia (Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, etc.): In these countries, domestic firms were weak and external pressure for trade liberalization was relatively strong. Instead of protecting local firms, these countries invited foreign firms to become the core industrial base. Initially protection and localization requirement were in place. Later, they were gradually removed. Their big problem is how to link local firms (still weak) with FDI firms, as supporting industries and receivers of international technology and management skills.

In the current situation, the Japan-Korea type industrialization has become almost impossible. The main reason is that the pressure for globalization is so strong that no country can maintain high tariffs in order to protect domestic industries. Latest comer countries must open up even faster than Thailand or Malaysia, even before they accumulate sufficient FDI base. The second reason is that local firms of most developing countries (including ASEAN) are generally much weaker than Japanese or Korean firms of a few decades ago.

Today, industrialization has become synonymous with inviting FDI. To receive more FDI, developing countries compete with each other by offering more attractive FDI environment and incentives, concluding free trade agreements, sending commercial missions to invite more investment, and so on. This is a big change from a few decades ago, when FDI by multinational corporations was regarded as economic invasion and exploitation. There were often violent popular protests against Japanese and Western firms investing in Southeast Asia. Now we have much less opposition. One reason for this is the great success of ASEAN type industrialization. Another reason is that foreign companies have learned to behave more carefully and respect local cultures and sensitivities compared with earlier times.

Trade liberalization is considered to be very important for inviting FDI (although I am not sure if this assumption is always valid empirically, or even theoretically). In East Asia, as in other areas, there are many frameworks for promoting free trade, at various levels including global, regional and bilateral.

WTO is a global organization. However, its effectiveness is seriously questioned in recent years. Its trade negotiations seem to proceed too slowly, and many developing countries feel that they are not receiving enough benefits while being asked to liberalize their trade regimes too quickly. Many officials and economists pay customary lip service to the importance of WTO, but they seem to have little trust on multilateral trade negotiations. I believe this is a sad state of affairs.

AFTA (ASEAN Free Trade Area) is a framework of 10 ASEAN countries (ASEAN in turn means the Association of South East Asian Nations). Its main purpose is to lower intra-regional tariffs (called the Common Effective Preferential Tariffs) to 5% or less by 2003 (latecomer countries have later targets) and remove all non-tariff barriers as well. ASEAN also has other cooperative schemes, including ASEAN Industrial Cooperation (AICO), ASEAN Investment Area (AIA), Initiative for ASEAN Integration (IAI), etc. One of the key objectives of ASEAN is to narrow the income gap between original ASEAN members, which are more developed, and newcomers of "CLMV" (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam), which are still very poor.

There was also APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) covering a wide range of countries, including East Asia, Russia, Australia, New Zealand, US, Canada, Mexico, Peru, etc). It set the trade liberalization goal of 2010 (for developed countries) and 2020 (for developing countries). But the momentum of APEC has been lost almost completely. The main reason for this is that it admitted too many countries with different interests.

Instead, ASEAN-Plus-Three (APT or ASEAN+3) has emerged as the most important East Asian cooperative framework. The "Three" here means Japan, China and Korea. It is noteworthy that it excludes Anglo-Saxon Pacific countries like the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. The ASEAN+3 has begun to operate as an institution for regional economic cooperation, integration and institutional harmonization. (Malaysia's former prime minister proposed this framework under a different name earlier, but it was rejected at that time).

At present, China has emerged as a very strong competitor and the "factory of the world," at least in the eyes of observers outside China. Not only are its products cheap, but the quality is also improving. For ASEAN countries, the rise of China is considered a very serious threat to their industrial development. Not only do they compete directly with Chinese products in the home and third markets (US, EU, Japan, etc) but they seem to be losing FDI to China. But China itself faces a serious challenge of domestic restructuring (SOEs, farm products, automobiles, consumer electronics, etc) as it implements WTO commitments. How serious and permanent is the Chinese threat? This is a hotly debated topic today. Since late 2003, China's economic boom (some say bubble) in construction and consumer goods is causing a worldwide shortage of energy and materials leading to price hikes in oil, steel, mineral ore, etc. The Chinese economy now greatly affects global prices and markets.

Recently, China has begun an aggressive economic diplomacy in Southeast Asia. It has targeted this region as an export market and an FDI destination. The Chinese government offers selective economic aid to the region (since China is not a member of the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC), it is not bound by the international code of conduct for ODA providers, including information disclosure, untying of aid, and aid coordination). China has proposed the China-ASEAN Free Trade Agreement, which surprised Japan and prompted it to make a similar proposal to ASEAN.

The third FDI hypothesis mentioned above also suggests that the government wishing to receive a great amount of FDI must understand the forces behind FDI dynamics very well. Recent research on trade and FDI points to two forces at play.

Agglomeration: this is an extension of trade theory with spatial external economies (scale merit in geographical concentration). Similar producers tend to gather in one place. For example, Silicon Valley in California attracts high-tech firms, while Akihabara in Tokyo is a huge collection of electronic outlets. Bangalore in India has accumulated software programmers while Guangdong in China has a concentration of garment and electronics industries. The importance of agglomeration as a source of locational advantage is now clearly recognized, although its microeconomic foundation (why they gather like that, theoretically?) is not well known yet. The important (and in a sense very shocking) thing about this is that the trade and investment pattern is determined mainly by wise FDI policy. Even a country with little capital and low educational achievements can attract FDI and industrialize. In other words, locational advantage is not a given thing, but it can be created relatively easily (if the government has the will and the skill).

Fragmentation: this means splitting of the production process of one product (from raw materials to final assembly) into many steps ("production blocks") which are undertaken in different locations. For example, to produce garment, cotton can be grown in Pakistan, spinning and weaving can be done in Taiwan, accessories may be produced in China, sewing and cutting can be done in Vietnam, and marketing can be done in the US. Each country can participate in the process in which it excels (namely, each country realizes its dynamic comparative advantage). But to do this, the costs of transportation, communication and production coordination (these are summarily called "service links") across countries must be sufficiently low. Otherwise, international division of labor will not be beneficial. Fragmentation is the opposite to vertical integration, where every process from upstream to downstream is undertaken within one country (or even within one factory). [In Central Asia, I have visited a huge factory that buys raw wool and sells jackets, with all intervening processes taking place under one giant roof, including designing of products.]

Agglomeration creates concentration, while fragmentation creates decentralization. On the surface, it seems that these forces are contradictory. But in reality, both are working at the same time.

One aspect of that is, some products are dominated by agglomeration while others are more strongly influenced by fragmentation. It depends on the product.

Another aspect is that situations change over time. As new products and new production methods are constantly introduced, the mix of agglomeration and fragmentation also shifts. This is particularly true for electronics and other high-tech industries.

More importantly, the two forces can simultaneously operate even for the same product. This is a case where each production process is concentrated in one country (hard disks in the Philippines, electric motors in Vietnam, software in USA, etc), but they together cooperate to produce one product (say, computers which are finally assembled in China). This is agglomeration at the level of each production process, but fragmentation among these processes. For each country, the key is to attract one slice of production process and create a large concentration of it domestically.

But this is an extremely dynamic and complex process, shifting from product to product, process to process and over time. Policy makers must have an understanding of this process, by closely working with foreign investors and getting latest information about changing industries and global markets. The government does not have to predict the future dynamics of industries (which is too difficult), but it must know how the trends are changing today and how businesses are responding. If you are unaware of industrial dynamics, you will waste a lot of money and time trying to attract industries which have no chance of coming.

For developing countries, what kind of policies are required in a world with free trade and fastidious FDI? I recommend the following. This advice comes from my experience of talking to the Vietnamese officials and enterprise managers in the last eleven years. It assumes a country which already receives a certain amount of FDI and hopes to receive more, above the critical mass, to industrialize and join the regional flying geese. [For those countries with little or no FDI absorption in manufacturing, a different strategy must be taken.]

First, understand FDI dynamics from the viewpoint of foreign investors (as discussed above). Too many officials think in terms of domestically set goals and requirements, and scare away potential investors. National goals and social concerns are certainly important, but they must be realized in a way that is consistent with FDI inflows.

Second, do not change rules after foreigners have already invested. Policy changes are fine, sometimes, especially for better. But for those who came earlier, the old rules should continue to apply so that they will not suddenly face an unfavorable situation ("grandfather clause"). Policy uncertainty is the biggest problem in Vietnam.

Third, do not try to have a vertically integrated industry, from raw materials to final assembly. In the age of globalization, no country can do that, not even developed ones. Target where your dynamic (i.e., future) comparative advantage is, and concentrate your effort on it.

Fourth, do not try to use domestically available natural resources unless they are highest quality and lowest cost (or nearly so) in the world. From the viewpoint of competitiveness, it is better to import best raw materials from the most efficient producers in the world.

Fifth, building supporting industries and technical transfer will take time. They must be done in proper speed and sequence. Hasty requirement of local contents not only violates WTO but also drives away foreign investors.

Six, accumulate assembly-type FDI first, without selectivity, even though domestic value-added is low. Next, as assemblers naturally desire to procure inputs domestically, promote or invite domestic and foreign parts suppliers. If successful, a virtuous circle between assembly and parts will emerge. Technology transfer will come after this, not before.

Seven, work cooperatively with foreign investors. Listen to their needs carefully (you don't have to accept all of their complaints; sometimes they are selfish). Set agreed goals for technical transfer, domestic procurement, etc. and design consistent supporting policies. Work with foreign investors toward these goals, and also solve any problems with them.

Eight, simple external opening (free trade and investment) is not enough. You must use targeted policies to create superior locational advantages and lower the costs of doing business in your country. This requires, among other things, improving domestic skills (production management, marketing, engineering--not just primary education), infrastructure, supporting institutions, efficient government services, good management of industrial and export processing zones (if any), and so on.

Nine, export-oriented FDI should be welcomed most, while domestically oriented FDI is a different story and must be treated differently. Do not attract them with high import protection. If they are already here with high protection, show them a tariff reduction schedule and give them incentive to lower costs. The final outcome (survive or exit) should be determined by global competition and efforts of individual enterprises. This is the same for protected local enterprises as well.

Every year, the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) conducts a survey on Japanese multinational firms. In 2004, the number of surveyed enterprises was 595. The survey period was July-Sep. 2004 which was followed up by firm visits and telephone interviews. The sample includes a wide range of industries from food processing to automobiles, from small to large firms, etc.

The main difference in 2004, as compared with previous years, is that Japanese firms have become more aggressive in expanding business both at home and abroad. This clearly reflects a better business condition and higher profits in recent years in Japan. Moreover, Japanese firms are now seriously concerned with building an optimal global production network instead of unilaterally transferring factories abroad. In fact, some activities (small-lot and high-value production and R&D) are returning to Japan from abroad.

China remains the most popular FDI destination but ASEAN also continues to be an important production location. Some firms worry about too much concentration in China (this worry is surely accelerated by the recent power shortages and anti-Japanese demonstrations in China). Thailand, India and Vietnam are the most popular destinations to diversify the China risk. However, while many firms have actual expansion plans for Thailand, they do not have concrete ideas for India and Vietnam; they are only potentially popular. Indonesia has gone down in popularity in recent years while Russia has become a little more popular than before.

|

Where do you produce "popular" (low-price) products? |

|||

| All manufacturing | Electronics | Automobile | |

| Japan | 19.3% | 5.5% | 18.6% |

| China | 8.6% | 16.5% | 2.3% |

| ASEAN | 8.0% | 7.3% | 9.3% |

| Japan & China | 20.0% | 17.4% | 16.3% |

| Japan & ASEAN | 8.6% | 5.5% | 12.8% |

| China & ASEAN | 15.0% | 29.4% | 14.0% |

| Japan, China & ASEAN | 20.7% | 18.3% | 26.7% |

| TOTAL | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

The production locations of low-end products are spread across the region: Japan, China and ASEAN all produce them. Many firms prefer to have more than one production location.

|

Where do you produce high value-added products? |

|||

| All manufacturing | Electronics | Automobile | |

| Japan | 73.0% | 70.4% | 73.6% |

| China | 2.1% | 1.9% | 0.0% |

| ASEAN | 1.9% | 4.6% | 0.0% |

| Japan & China | 9.9% | 10.2% | 11.5% |

| Japan & ASEAN | 5.1% | 3.7% | 9.2% |

| China & ASEAN | 0.5% | 0.0% | 1.1% |

| Japan, China & ASEAN | 7.4% | 9.3% | 4.6% |

| TOTAL | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

High-end products are predominantly produced in Japan. Producing such products in China or ASEAN still remains rare.

|

Where do you plan to expand business in the next

three years? |

|||||

| 1 | China (Central Coast) | 68.9% | 8 | Taiwan | 21.3% |

| 2 | Thailand | 47.8% | 9 | Eastern Europe | 17.4% |

| 3 | China (Southern Coast) | 47.6% | 10 | Vietnam | 15.9% |

| 4 | North America | 44.3% | 11 | India | 15.5% |

| 5 | China (Northern Coast) | 35.0% | 12 | Malaysia | 15.5% |

| 6 | EU15 | 31.5% | 13 | China (Northeast) | 13.7% |

| 7 | Korea | 24.2% | 14 | Singapore | 12.0% |

China remains a very popular FDI destination in the near future, but Thailand is also very popular as the ASEAN production base.

|

Do you plan to withdraw from any countries? |

|

| Hong Kong | 11 |

| Taiwan | 10 |

| Indonesia | 10 |

| Malaysia | 10 |

| Singapore | 9 |

| Philippines | 8 |

| EU15 | 8 |

| North America | 7 |

| Other | 14 |

A small number of firms want to withdraw from these areas with relatively high cost. These cases can be classified into three types: (i) closing operation entirely (38 cases); (ii) moving to another country (37 cases, mainly to China); and (iii) moving back to Japan (10 cases).

|

What is (will be) the risk of doing business in

China? |

||

| At present (within 1 year) | In future (within 5 years) | |

| Shortage of electricity supply | 56.5% | 33.4% |

| Price increase in energy & materials | 36.5% | 38.2% |

| Violation of intellectual property rights | 29.3% | 32.5% |

| Logistic and transportation problem | 11.8% | 17.0% |

| Frequent changes in FDI policy | 9.2% | 40.9% |

| Appreciation of Yuan (Chinese currency) | 8.5% | 67.7% |

| Shortage of industrial water supply | 3.5% | 13.4% |

| Business downturn, market shrinkage | 1.8% | 33.8% |

Power shortages, input cost inflation and IPR violation are big headaches now and in the future. In addition, policy instability, RMB revaluation and recession loom large in the future.

|

What are the greatest merits and demerits of the

following countries? |

|||

| Top 3 merits | Top 3 demerits | Have concrete plans (# of firms) |

|

| (1) China | -Future market potential -Cheap labor -Supporting industries |

-Ambiguity of laws -Violation of IRP -Unrecoverable receivables |

318 |

| (2) Thailand | -Future market potential -Cheap labor -Stable politics & society |

-Competition with other firms -Rising labor cost -Lack of managers |

83 |

| (3) India | -Future market potential -Cheap labor -High-quality human resource |

-Lack of infrastructure -Lack of information -Crime & social instability |

23 |

| (4) Vietnam | -Cheap labor -Future market potential -High-quality human resource |

-Undeveloped legal system -Ambiguity of laws -Lack of infrastructure |

30 |

| (5) USA | -Current market size -Future market potential -Good infrastructure |

-Competition with other firms -Rising labor cost -Labor problems |

58 |

| (6) Russia | -Future market potential -Cheap labor -High-quality human resource |

-Crime & social instability -Lack of information -Undeveloped legal system |

9 |

| (7) Indonesia | -Cheap labor -Future market potential -Export base for third market |

-Crime & social instability -Competition with other firms -Lack of managers |

23 |

Japanese firms are generally attracted by market size and low labor cost. On the demerit side, legal uncertainty is a big problem in China and Vietnam; and lack of infrastructure is a problem in India, Vietnam and Russia. Social instability and personal safety is a problem in India, Russia and Indonesia.

<References>

Ohno, Kenichi, "The East Asian Experience of Economic Development and Cooperation," chapter 4, East Asian Growth and Japanese Aid Strategy, GRIPS Development Forum, 2003.

Ohno, Kenichi, "Designing a Comprehensive and Realistic Industrial Strategy," Vietnam Development Forum Discussion Paper no.1 (June 2004). Presented to the Vietnamese Ministry of Industry in February 2004. paper slides

Ohno, Kenichi, and Nguyen Van Thuong, eds, Improving Industrial Policy Formulation, Vietnam Development Forum, published by the Publishing House of Political Theory, Hanoi, 2005.

Ohno, K., "Supporting Industries: Some analytical points for consideration," draft, April 2005. paper

Ohno, Kenichi, The Economic Development of Japan: The Path Traveled by Japan as a Developing Country, GRIPS Development Forum, 2006 (see box "The road ahead for Japanese enterprises," pp.213-216).

T. Marukami, T. Mimura, H. Saito and M. Suzuki, "The Survey Report on the Overseas Business Expansion of Japanese Manufacturing Firms: The Results of the 16th FDI Questionnaire Survey," Kaihatsu Kinyu Kenkyushoho (Journal of JBIC Institute), no.22, February 2005 (Japanese).

Satake, Takanori, Eiichi Sekine, and Mayumi Suzuki, "The Survey Report on the Overseas Business Expansion of Japanese Manufacturing Firms: The Results of the 17th FDI Questionnaire Survey," Kaihatsu Kinyu Kenkyushoho (Journal of JBIC Institute), no.28, February 2006 (Japanese).

VDF Report, "Supporting Industries in Vietnam from the Perspective of Japanese Manufacturing Firms," draft, April 2006. draft report